Stories from the Petter Photos

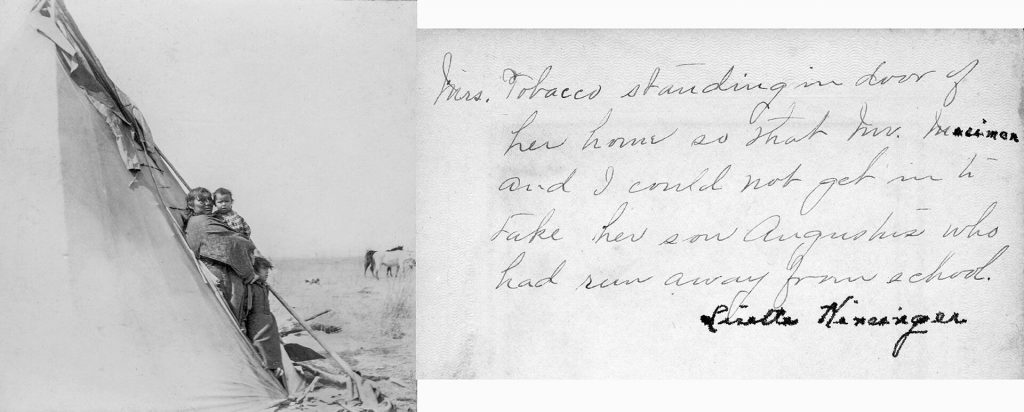

Mrs. Tobacco’s son Augustus didn’t want to be in school, so he ran home to his tepee. School superintendent Samuel K. Mosiman and his cousin, school nurse Lisette Kinsinger, pursued the boy to bring him back to school. As usual, Lisette carried her camera. When they reached the tepee, Mrs. Tobacco stood in the doorway, supporting her son’s decision.

We don’t know the outcome of this standoff, but it illustrates the tension between white missionaries and the Cheyenne people of Oklahoma. The Mennonite Mission School at Cantonment operated from 1883 to 1901 and was part of a nationwide movement of mostly well-meaning folks who sought to bring Native Americans into the mainstream of the white American way of life: learn English, adopt private ownership of land, become Christians, reject their Native culture.

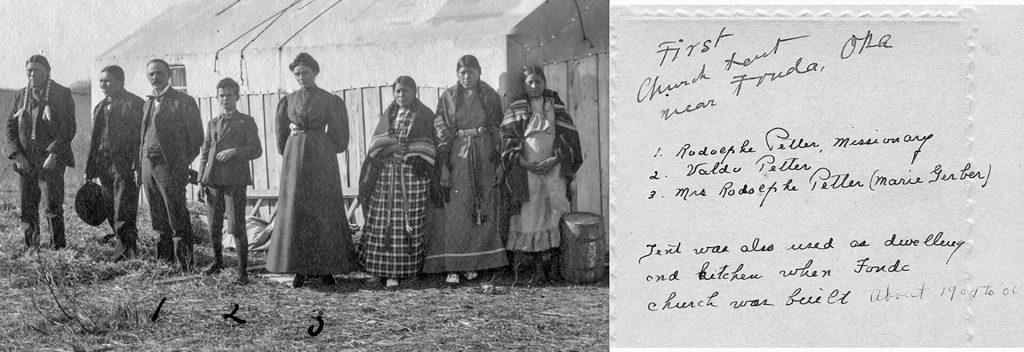

A central figure to the Oklahoma and Montana stories of Mennonite efforts with the Cheyenne was Rodolphe Petter. He was born into a Swiss family who were nominally Reformed, married a Swiss Mennonite girl named Marie Gerber, and answered the call of the General Conference Foreign Mission Board to work with the Southern Cheyenne in Oklahoma Territory. Rodolphe and Marie arrived in Cantonment, Oklahoma, on Sept. 30, 1891. After Marie’s death from tuberculosis in 1910, Rodolphe married Bertha Elise Kinsinger, a teacher at the Mennonite Mission School since 1896. Rodolphe and Bertha moved from Oklahoma to Montana in 1916, where they spent the rest of their life working with the Northern Cheyenne people.

Petter was the driving force behind the creation of the first Cheyenne-English dictionary. He led the process of translating much of the Bible into Cheyenne as well as Pilgrim’s Progress and other materials. Though only Rodolphe’s name is on the dictionary, Bertha also did translation work, Harvey Whiteshield in Oklahoma was Rodolphe’s Cheyenne tutor and translator, and Anna Wolfname in Montana was not only Rodolphe’s typist but also a trusted consultant for the translation work.

Bertha made sure her husband’s work would not be forgotten. She saved everything. In the Mennonite Library and Archives (MLA) at Bethel College, there are dozens of boxes of letters, documents, books, and photographs that chronicle the education and missionary efforts carried out by Rodolphe, his wives and family members, and many other Mennonite missionaries and volunteers among the Cheyenne.

The 3,082 Petter photographs had never been digitized until MLA director John Thiesen gave that task to me as a volunteer in 2017. More than 1,800 old and brittle negatives came out of their storage refrigerator for scanning, as well as envelopes stuffed full of random prints. I had worked at this task for several weeks before I realized I was sitting at Rodolphe Petter’s desk in the MLA. I imagined his presence as I worked, wishing he could explain each photo.

After a year of scanning and an equal number of hours in Photoshop®, the entire Petter collection is available online at https://mlabethelks.org/petter-photos/. Each photo tells a story, but many of the prints also had writing on the back explaining the photo on the front. Those written notes, most often in the disconnected cursive letters that mark Bertha Kinsinger Petter’s distinctive handwriting, add new details and depth to the Petter story.

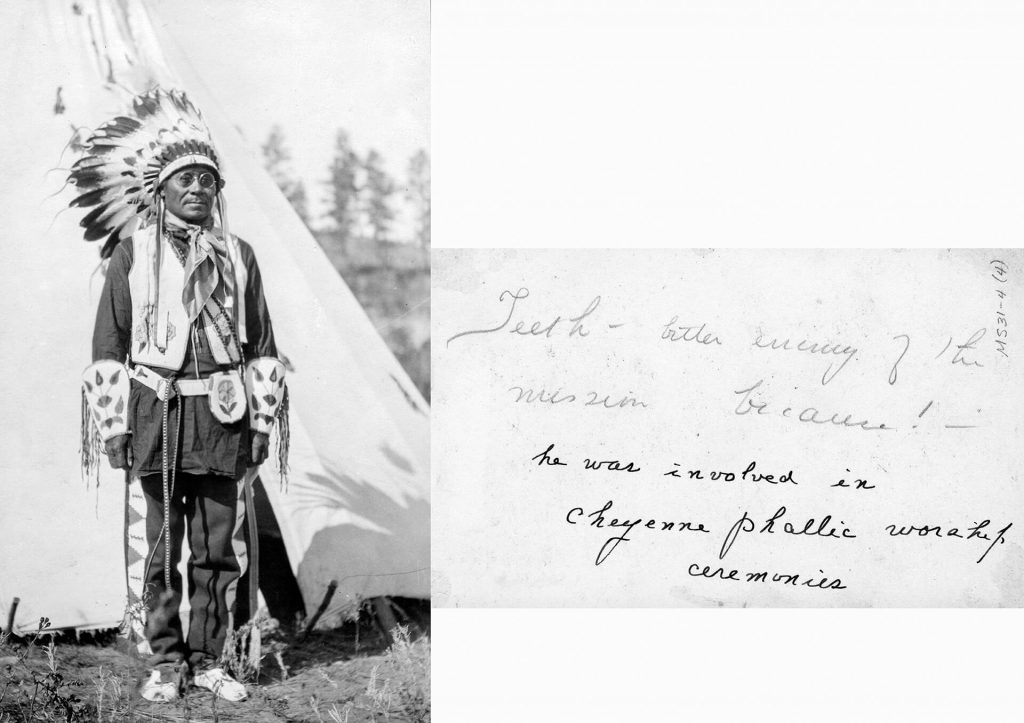

Bertha Kinsinger Petter labeled this Cheyenne man named “Teeth” as a “bitter enemy of the Mission.” She cites his involvement in “Cheyenne phallic worship ceremonies” as the basis for his opposition. Rodolphe Petter’s Cheyenne-English dictionary names “phallic worship or veneration of the generative power” as a central component of the Sun Dance, the most important ceremony for all Plains Indians. Not only did missionaries seek to stop the Sun Dance for theological reasons, but the U.S. government, through the Bureau of Indian Affairs, also outlawed it as part of the national effort to eliminate Native culture. The government prohibition on the Sun Dance was reversed in 1934. Some tribes today still practice the Sun Dance as a prayer for life, renewal and thanksgiving.

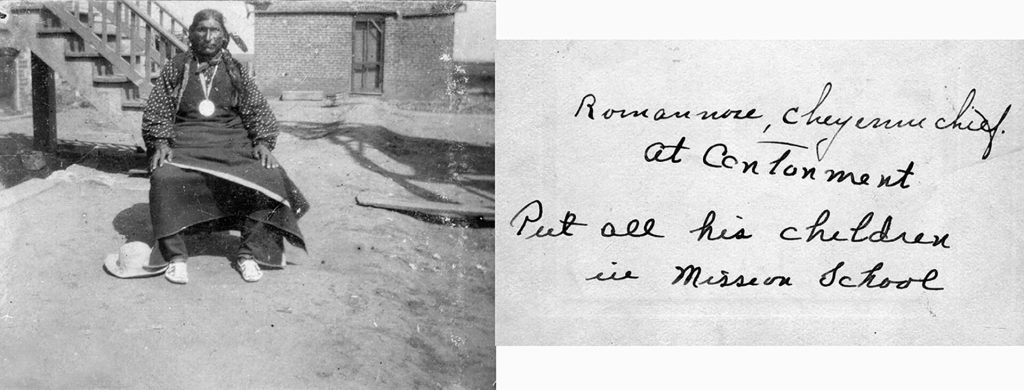

Cheyenne leaders were not of one mind about how to respond to the pressures to assimilate into white culture. Chief Henry Roman Nose (1856-1917) believed that education and training provided the way forward for his people. Setting an example, he sent all his children to the Mennonite Mission School in Cantonment. He worked at retaining elements of Cheyenne culture while helping his people transition to a non-nomadic way of life. The land allotment he accepted from the government is now part of Roman Nose State Park in Oklahoma, named in his honor.

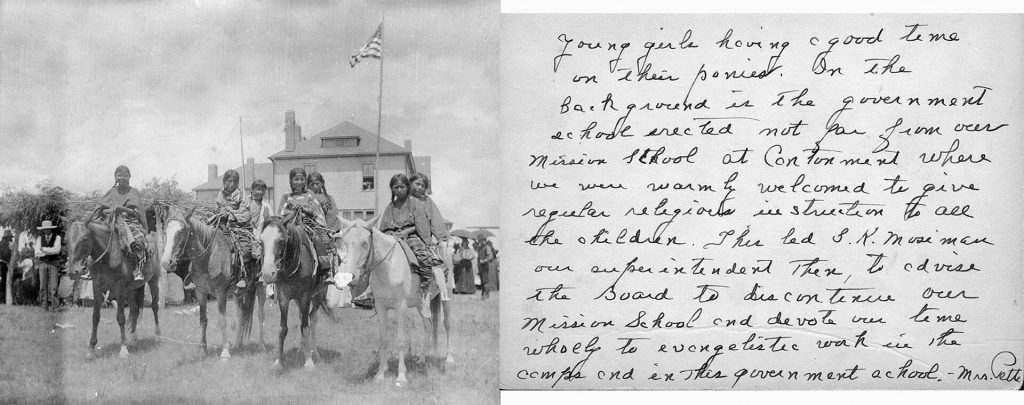

This photo of young Cheyenne girls on their horses in front of the government-run Indian boarding school at Cantonment prompted Bertha to explain the change of focus of Mennonites in Oklahoma from education to evangelism. The new government boarding school replaced the Mennonite Mission School that had operated for 18 years. Bertha credits school superintendent Samuel Mosiman for leading the transition from just the education of children to a broad-based evangelism among both children and adults. She affirms the warm welcome the government boarding school officials gave to Mennonite missionaries to teach Bible classes in the government school.

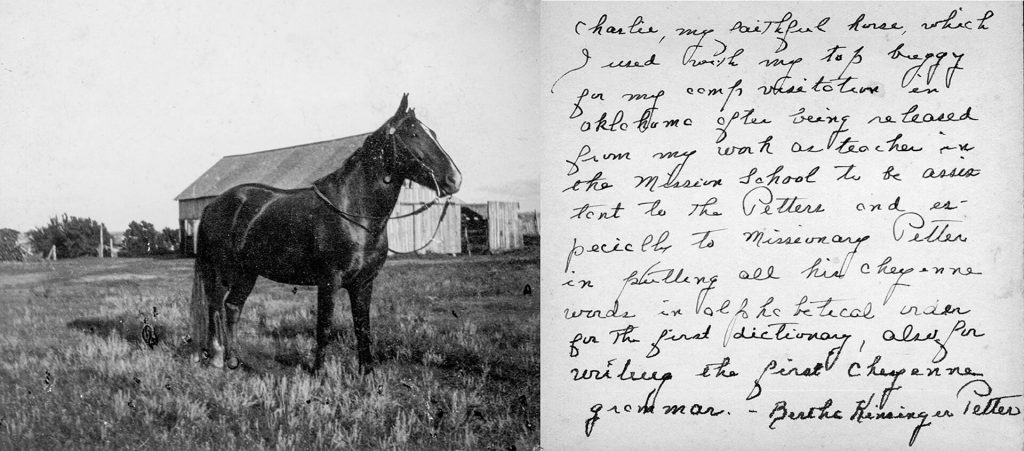

Bertha uses the photo of her beloved horse Charlie to explain her work: “Charlie, my faithful horse which I used with my top buggy for my camp visitation in Oklahoma after being released from my work as teacher in the Mission School to be assistant to the Petters and especially to Missionary Petter in putting all his Cheyenne words in alphabetical order for the first dictionary, also for writing the first Cheyenne grammar.”

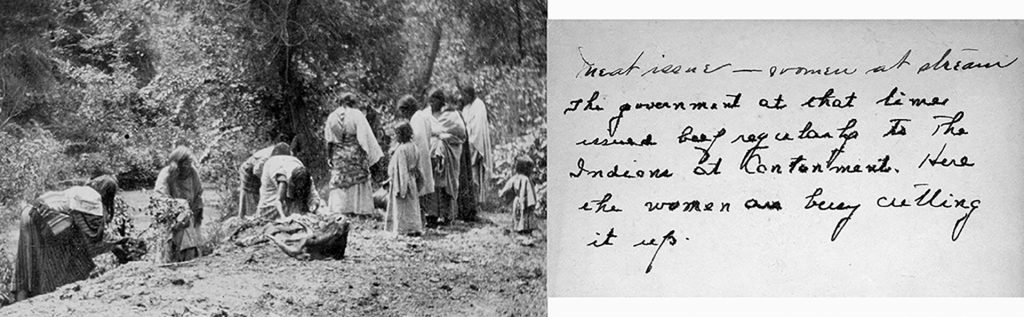

The forced move of the Cheyenne from their independent life on the plains to the Oklahoma reservation cut them off from their ability to sustain themselves through the bison hunt. In Oklahoma, they were almost completely dependent on the government for food. Besides “domestic rations” of flour, sugar, coffee, bacon, and dried beans, the government occasionally provided beef. Neither this photo of Cheyenne women cutting up beef outdoors nor Bertha’s note on the back reveals the procedural details for the Oklahoma “beef issue,” but it was common practice for the government to procure a herd of cattle, then turn the cattle loose so they could be pursued and killed by Indian men on horseback, an inglorious recapitulation of the bison hunt. Indian families would dress out the animals where they fell, load the meat into wagons and dry much of it for storage.1

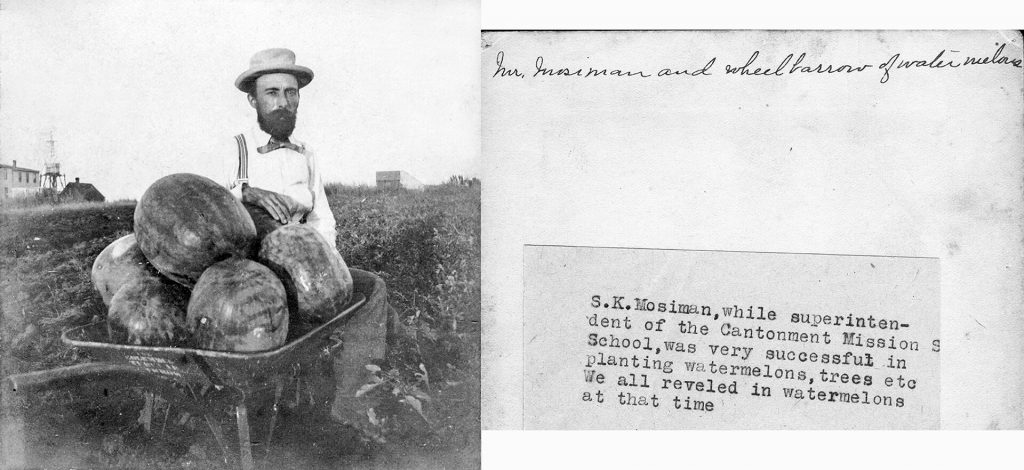

Samuel Kinsinger Mosiman came to Oklahoma in 1897 as superintendent of the Mennonite Mission School. Besides his educational duties during the next four years, he planted orchards around the school and grew tasty watermelons of a size not currently found in today’s grocery stores. Mosiman’s experience in Oklahoma was part of the path toward his 25-year presidency of Bluffton (Ohio) College from 1910-35.

A few miles northwest of the Cantonment location was the outstation of Fonda. In 1907, the Petter family, probably with the help of the supportive Chief Mower, built a tent structure that served as the Petter house as well as a worship space until a more permanent wooden chapel could be built. The photo shows Cheyenne people on either side of Rodolphe Petter, son Valdo, and Marie Gerber Petter. Marie would die three years later of tuberculosis. The Petters’ older daughter Olga is not in this photo.

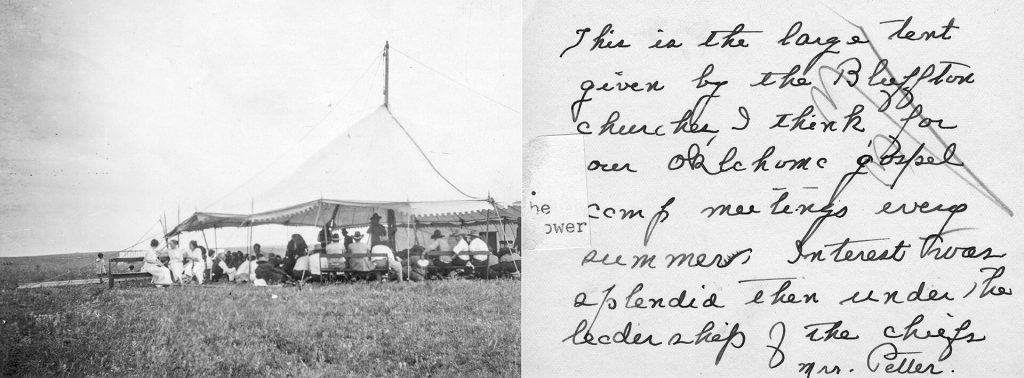

Mennonites from Bluffton, Ohio, supported the Oklahoma mission work by raising funds to purchase a large tent that was used for Cheyenne evangelistic camp meetings every summer. Bertha credits the high interest of the Cheyenne people to the support and leadership of the local chiefs.

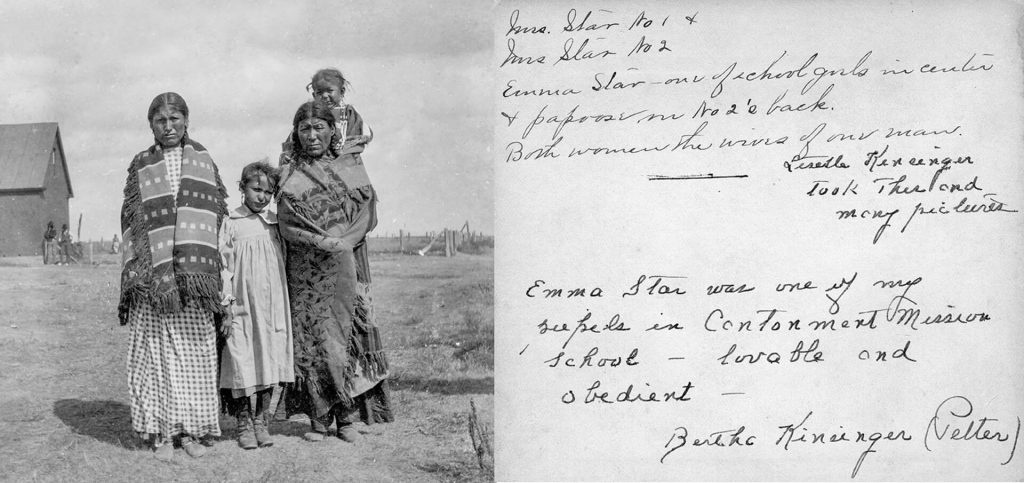

Mrs. Star #1 and Mrs. Star #2 shared one husband. Bertha affirms daughter Emma Star as “lovable and obedient” and also credits Lisette Kinsinger as a frequent photographer.

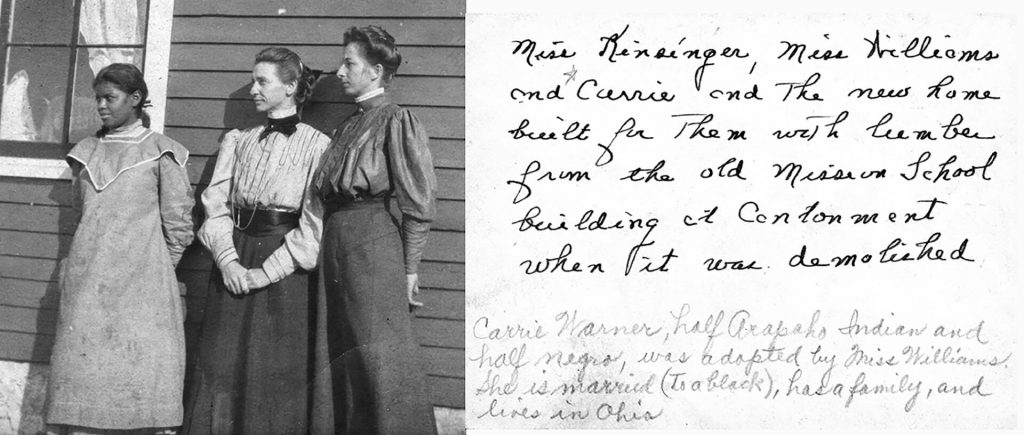

This is a photo of a household. Bertha Kinsinger (right) recruited her close friend Agnes Williams (center) to join her in the Oklahoma missionary work. Bertha and Agnes were childhood friends, members of the same Ohio congregation. They were both teachers at the Mennonite Mission School. When the school was closed in 1901 and then demolished, the lumber was used to build this house for them nearby. Bertha and Agnes had sole responsibility for the evangelism work in nearby Clinton from 1907-09, preaching, teaching, doing funerals, visiting, and fulfilling all missionary duties.

To the left is Carrie Warner, the third member of the household. Carrie’s father was a slave who ran away to live with the Indians when he was a boy. Carrie’s mother was Arapaho. Carrie was brought to the Mennonites in Cantonment after her father died, when she was 18 months old. Various missionaries, including Barbara Lugibiehl, took care of her, but Agnes Williams adopted Carrie as her own. Bertha, Agnes and Carrie lived together until 16-year-old Carrie went to Hampton Institute in Virginia and Bertha decided (after months of internal struggle about whether or not to give up her life of “single blessedness”) to accept Rodolphe Petter’s marriage proposal.

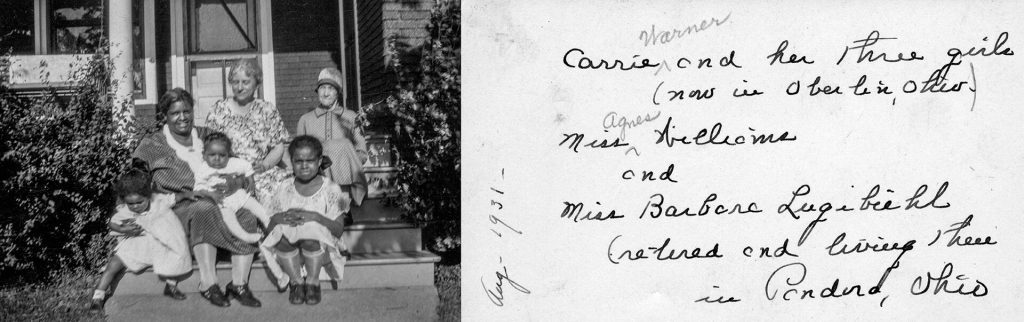

After four years of study at Hampton, Carrie moved to Oberlin, Ohio, where she married, had three children and became a beloved cook in the Oberlin community and at Oberlin College.2 She knew about Oberlin because Rodolphe and Marie Gerber Petter had studied English there for a year before going to Oklahoma.

The missionaries stayed in touch with Carrie. The photo below shows Agnes Williams and Barbara Lugibiehl visiting Carrie Warner Smith and her three daughters in 1931 in Oberlin.

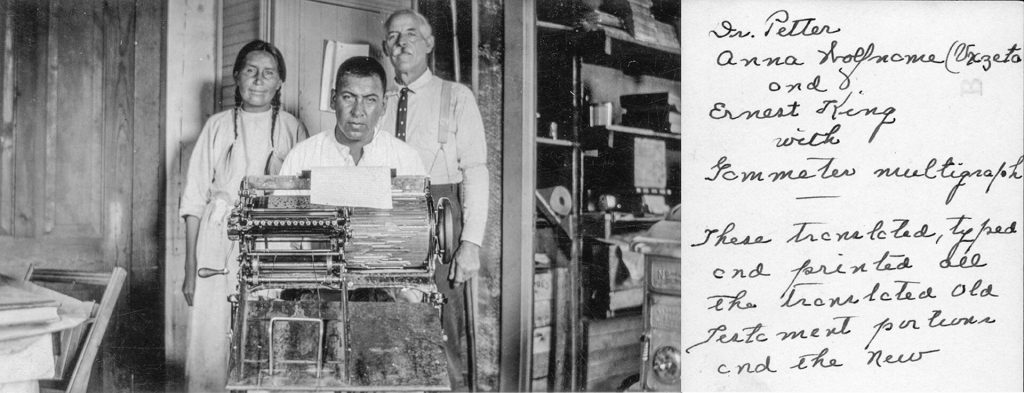

This iconic photo of Rodolphe Petter and his two most trusted Montana helpers includes the Gammeter multigraph printing machine, now housed in the Kauffman Museum in North Newton, Kan. Ernest King was a Mexican-Cheyenne man with mechanical skills, and Anna Wolfname (Vxzeta) was Rodolphe’s typist, copy editor, and deeply trusted helper. Rodolphe so valued Anna’s help with his continuing translation work that he took Anna and her children along with his own family when they traveled to Kettle Falls, Washington, where the Petters had a large apple orchard.

My year-long experience with the 3,000-plus Petter photographs gave me the opportunity to do some fun detective work. Who is in this photo? What are they doing and why? Where is it? What’s the backstory?

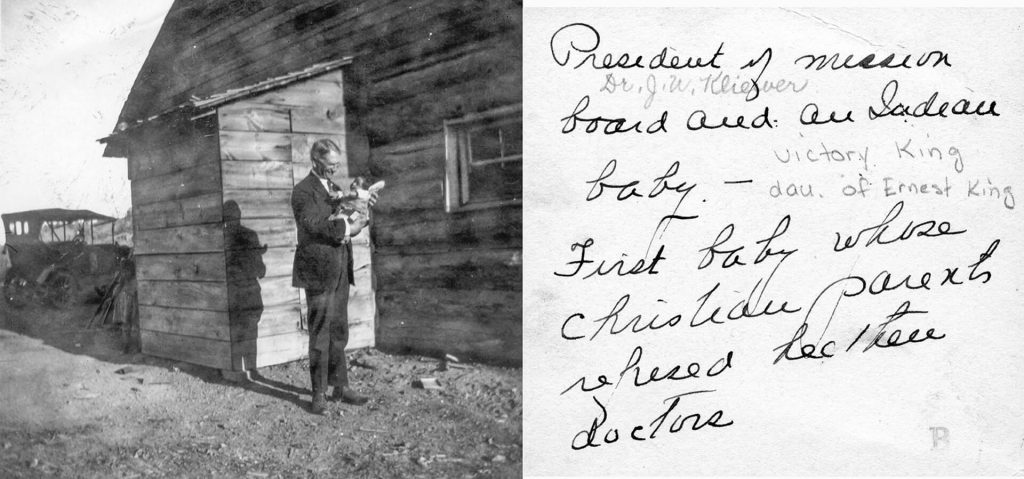

The first time I saw this print of a tall man holding a baby, I turned it over. But the back of the print was blank. Months later, I discovered another print of the same photo, turned it over and found the answer I was looking for.

The tall man is president of the Mennonite Mission Board, Dr. J.W. Kliewer. He had served as a pastor in Wadsworth, Ohio, and in Berne, Ind. From 1911 to 1920, he was president of Bethel College, and he served on the Foreign Mission Board of the General Conference from 1908-35. He is holding this Cheyenne baby with pride for, as Bertha writes, this was the first Cheyenne baby “whose Christians parents refused heathen doctors.” The missionaries saw this baby as a positive milestone in their work.

As a further note from someone else’s hand makes clear, the baby held by Dr. Kliewer was Victory King, the daughter of Ernest King, who operated and maintained the multigraph printing machine for the Petters.

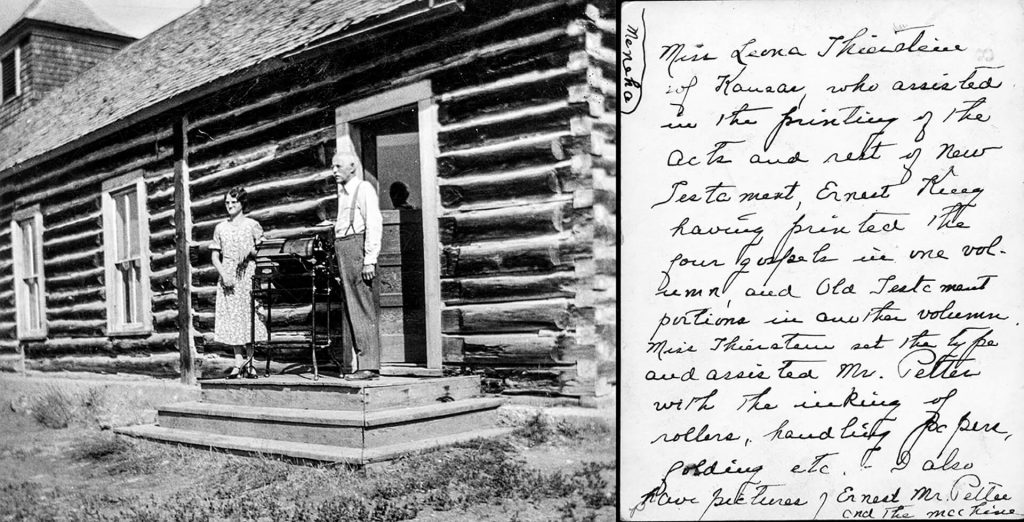

Many short- and long-term missionaries and helpers worked with the Petters in both Oklahoma and Montana. Leona Thierstein of Whitewater, Kan., is standing with Rodolphe Petter and the multigraph machine outside the door of Rodolphe’s study in the Lame Deer Chapel in Montana. In her note, Bertha adds new details about the process of printing:

“Miss Leona Thierstein of Kansas, who assisted in the printing of the Acts and rest of New Testament, Ernest King having printed the four gospels in one volume, and Old Testament portions in another volume. Miss Thierstein set the type and assisted Mr. Petter with the inking of the rollers, handling papers, folding, etc.”

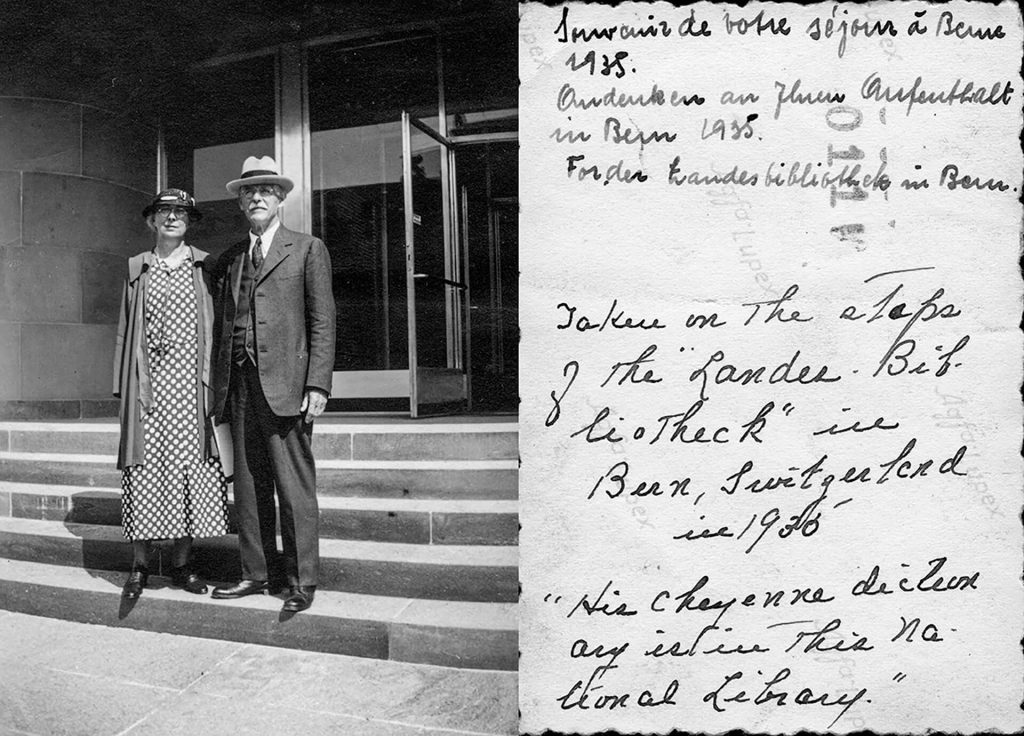

In both 1935 and 1939, money was raised to help Rodolphe and Bertha Petter visit Europe, particularly Switzerland, Rodolphe’s homeland.

In 1935, Rodolphe and Bertha stood on the steps of the Bern library that held a copy of his life’s work, the Cheyenne-English dictionary.

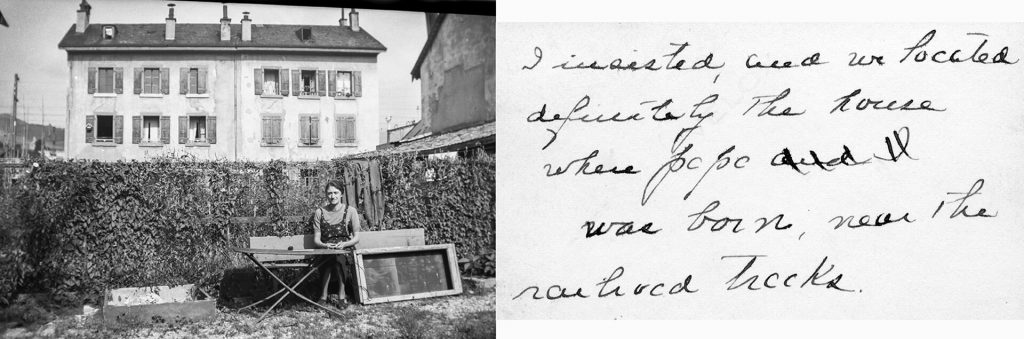

The second photo was taken in Vevey, Switzerland, Rodolphe’s hometown on the shores of Lake Geneva. With her step-children Olga and Valdo in mind, Bertha celebrates how her persistence resulted in finding Rodolphe’s birthplace: “I insisted, and we located definitely the house where papa was born, near the railroad tracks.”

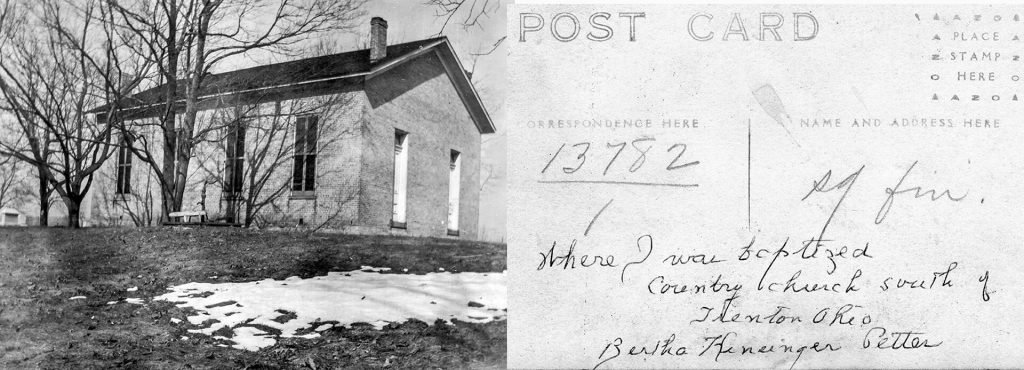

This is the meetinghouse of the Apostolic Mennonite Church, the Hessian congregation near Trenton, Ohio, where Bertha Kinsinger was baptized. This congregation played an outsized role in Mennonite work with the Cheyenne, for from this congregation came not only Bertha Kinsinger, but also her close friend Agnes Williams and her cousins Lisette Kinsinger and Samuel Kinsinger Mosiman. In addition, the $500 donation used to buy the Gammeter multigraph printing machine came from Catherine Bender, also a member of this congregation.3

*****

I didn’t consider my work finished until I had seen where the Petters lived and worked. So my wife, Florence, and I traveled to the busy little Cheyenne town of Lame Deer, Mont. In the Lame Deer post office, neither the young man at the front desk nor an older Cheyenne woman in the back had ever heard of Rodolphe Petter.

At the Cantonment location in Oklahoma, on a hill a few miles northwest of the town of Canton, I found the grave of Marie Petter. The top had fallen over into the long grass, so I set it back on its pedestal. Except for the gravestones and trees, the hill was empty.