Field Language: Poetry and Painting in Conversation

What follows is a conversation (necessarily held via e-mail) involving Mennonite Life editor Melanie Zuercher, and Julia Spicher Kasdorf and Christopher Reed, who have collaborated with Joyce Robinson, curator at Penn State University’s Palmer Museum of Art, and the Woodmere Museum in Philadelphia, on exhibitions and a catalogue of essays about the paintings and poetry of Warren and Jane Rohrer:

“Field Language: The Painting and Poetry of Jane and Warren Rohrer,” Palmer Museum of Art, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pa. – 2021, to be determined (check the museum’s website for updates)

Field Language: The Painting and Poetry of Jane and Warren Rohrer, Julia Spicher Kasdorf, Christopher Reed, Joyce Henri Robinson, editors (Palmer Museum of Art, 2020, distributed by Pennsylvania State University Press)

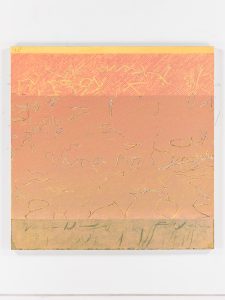

Warren Rohrer, “Field: 20 Minutes in June (1990).” Courtesy of Locks Gallery, © the artist. Photo by Tom Powel Imaging.

Red Flannel

It says on page thirty-five

of Red Flannel Rag

my great uncle Luther Kirkpatrick

was the meanest man in Hopkins Gap.

The poetry of the holler

is the subject here

and I must return there soon

to see if it still takes twenty minutes in June

from the instant sunlight leaves the valley floor

until darkness falls on the faded clapboard houses

and the clatter of moonshine stills.

Luther, what am I to do with you

now that you have been carried out of the mountains in a book

but seat you in my barrow

with all the other ancestors

I wheel daily along the streets of my life

to, say, the Art Museum

where you might feel at home

with the villagers of Hieronymus Bosch.

– Jane Rohrer

“Red Flannel” is reprinted from Acquiring Land: Late Poems by Jane Rohrer (DreamSeeker Books, imprint of Cascadia Publishing House, 2020) and is used by permission of the publisher.

ML: Julia, would you talk about your connection to Warren and Jane? Didn’t you write a poem for Warren?

JK: Back in 1992, around the time my first book [Sleeping Preacher] was published, a committee at Community Mennonite Church of Lancaster [Pa.] decided to offer a series of Sunday morning talks by people from Mennonite backgrounds who were involved in non-traditional Mennonite jobs – by which, I guess, they meant not agriculture or helping professions – so a judge, a fashion designer (whom they grilled about off-shore sweatshop labor), a painter, a poet, etc. And out of that Lois (Frey) Gray, a counselor on the planning committee, formulated a study group that came to be called “Mennonite Roots Pursuing Creativity,” which met for a few years, several times a year, for a full day [each time], and talked into a tape recorder.

Initially, [Lois] wanted to know how a conservative upbringing, what she termed “positive marginality,” contributed to “highly creative” life. (Lois presented her findings at “Quiet in the Land? Women of Anabaptist Traditions in Historical Perspective” in 1995 and later published an article in Mennonot.) Other members of the study group included narrative historian John L. Ruth, anthropologist Elmer Miller, fashion designer Julie Musselman, painter Warren Rohrer, and botanist and amateur theologian Carl Keener, who dropped out early on. Spouses were also invited, so that’s how I met Jane, who contributed to the conversation, too.

I was far younger than the rest of them, and the Rohrers made a deep impression at a time when I had just published my first book, and some poems in The New Yorker, and was earnestly trying to negotiate a life between my background and the literary world in New York City, where I was living, married to an art student who also grew up Mennonite. As Warren’s leukemia progressed, the group seemed to shift in focus from discussions about the impact of identity on all of us to support for his end-of-life reckoning with a severe period in the Mennonite Church – during and after World War II – and with a family that never really understood his work. One of our last meetings occurred in the Locks Gallery during his final exhibition of the Field Language paintings.

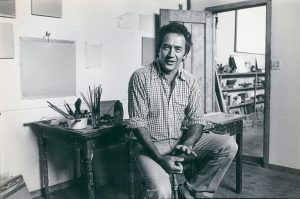

Warren Rohrer, c. 1980s; courtesy of the Rohrer family

Yes, “Boutstrophedon,” a poem that appears in Eve’s Striptease, was written for Warren, who taught me the meaning of that word. The poem describes the modernist life of leaving home to become an artist who then makes backward-glancing work. It’s a sestina, a fixed form that involves an elaborate, shifting pattern of repetition. In a gracious letter of response, Warren broke down the pattern and mapped it out numerically – which is similar to the way he set up intricate grids for his gorgeous, spontaneous-seeming paintings.

As I listen to the tapes Lois made at those meetings, I’m ashamed to say that what we called “the Creativity Group” mainly amplified the male voices that dominated the conversation. It wasn’t until Jane’s first book of poems, Life After Death, in 2002, and Ann Hostetler’s 2003 Mennonite Quarterly Review article recovering the work of three pioneering Mennonite poets – who all happen to have been women – that I realized the significance of Jane’s literary work. Warren had an esteemed career during his lifetime. These exhibitions and publications are now giving Jane her due as an artist, too, and not just as the person who supported Warren’s vocation, although she did do that. I’m so glad that Jane – who was born in 1928 – has lived long enough to see the publication of Acquiring Land and these exhibitions, online materials and catalogue that all include her poetry.

Anyway, I got involved initially because the curators of a small exhibition of Warren’s work at the Allentown Museum asked me to speak there about Jane’s poetry in 2016. Out of that experience, I knew there was more work to do, but I also knew that I couldn’t do it alone. My colleague Chris Reed is trained as an art historian and had collaborated on curating exhibitions about the Bloomsbury Group and about japonisme, which are topics that connect literature and visual art, so I knew he would be able to pull something like this off.

CR: Here I have to dive in to say that when Julia sat me down with a book, produced by the Locks Gallery, of reproductions of what immediately struck me as amazingly beautiful paintings, I thought that, with her connections to the Rohrers and her experience of grant writing, she would be able to pull this off.

And indeed, we are the grateful beneficiaries of a major grant from Penn State to support the humanities through interdisciplinary cooperation and community outreach. That grant helped us – working with Joyce Henri Robinson, from the Palmer Museum of Art here on Penn State’s main campus – to borrow paintings from private lenders and major museums and to partner with the Woodmere Museum of Art in Philadelphia on a companion exhibition. We were also supported with smaller grants, one from the art history department to help ensure the high production values of our catalog, and one from the Max Kade Foundation that enabled us to bring the authors of our catalogue essays together for a day of very fruitful discussion.

JK: Yes, it was something like a scholarly “frolic,” all of us commenting on one another’s essay drafts – a great pleasure and privilege to get together and work together.

ML: Why put these paintings and poems together now? Where did the idea to pair Warren and Jane come from? Aside from the fact that they were partners in life and work, I’m talking more about the choice of putting images and words together. What are some things you hope viewers will take from the exhibition?

CR: I don’t think we’re putting the images and words together! They developed together, so all we’re doing is not pulling them apart the way academic disciplines so often do.

The interaction of authors and artists is a fundamental – if under-recognized – characteristic of modernism. There’s a lovely remark of Virginia Woolf’s claiming that if every Cézanne painting disappeared, people in the future would know he existed just by reading Proust: “Were all modern paintings to be destroyed, a critic of the twenty-fifth century would be able to deduce from the works of Proust alone the existence of Matisse, Cézanne, Derain, and Picasso; he would be able to say with those books before him that painters of the highest originality and power must be covering canvas after canvas, squeezing tube after tube, in the room next door.”

Certainly one thing we hope our audiences of the exhibitions and readers of the catalogue will think about is the relationship between painting and poetry in general and, as in this case, when the paintings and poems come from a particular place – meaning not just a location, or set of locations, but a cultural situation–the relationship between art and life.

Jane Rohrer, c. 1970s; courtesy of the Rohrer family

Both the exhibition and the catalogue offer juxtapositions of particular paintings and poems designed to provoke readers to speculate about their connections. How do these paintings and poems compel us to see differently? How, for instance, might Warren’s evolution toward a kind of minimalism compare to a poem like Jane’s “Metaphor” (one of my favorites), which is about remembering the farm they lived on for 20 years. It concludes by describing how a feeling of longing is brought on by hearing “a single word” at a party:

Was it orchard?

Was it pond,

Or simply hill?

The progression of increasingly simple words – orchard, pond, hill, might be correlated with Warren’s career-long evolution from realism to abstraction, or to his use of repeated strokes of paint. What seems to be at issue in both the poem and his paintings is how much can be conveyed by how little.

ML: As we all face the reality of climate change and encroaching climate disaster, what do Warren and Jane’s connections to their rural Mennonite roots have to say about climate justice and about indigenous connections to land? They were clearly both affected – Warren most visibly so – by where they came from and by the natural world. What is the broader significance of that?

JK: My hope is that people will leave these exhibitions with a different sense of the agriculturally altered landscape. Looking at Warren’s paintings has certainly changed the way I look at farmers’ fields around the town where I live. His paintings have made me aware of the “culture” in agriculture, by which I mean human labor in relationship with the land. Some people believe that the Anthropocene began with the industrial revolution, and others say it started with the advent of agriculture. I’m not about to enter that debate, but our catalogue includes a beautiful essay by agricultural historian Sally McMurry who describes changes in agricultural practices in Lancaster County during the 20th century and considers them in relation to Warren’s work.

As a side note, I’ll also say that Warren and Jane bought the 18th-century Christiana [Pa.] farmstead from Mennonite farmers in 1961 and rented the fields to their Amish neighbors, and Jane describes their labor in poems in Life After Death. In the early 1980s, the Rohrers sold the farm to a Mennonite veterinarian Harley Kooker and his wife, Kate, who have since put the lower field in a soil conservation program. Before that land came into Mennonite hands, it belonged to Quakers, and the small town of Christiana nearby is probably best known for the Christiana Riot (Resistance) of 1851 in opposition to the Fugitive Slave Act.

About 30 years ago, the late author Jerome Badanes, bemoaning the cultural impact of the establishment of the state of Israel on Jewish culture, told me, “If you own land, you have blood on your hands!” That was the first time I considered the violent side of my (Mennonite?) romance with the land. I think Jane has long been on to this idea. The title poem of her most recent book, Acquiring Land, refuses an ethic of property, dismissing the 1,000 acres her father owned in the Shenandoah Valley, and instead embraces travel as a way of acquiring “more and more addresses.”

ML: The question we are pretty much being required to ask now (it’s decades, even generations, overdue): What is the social value of an exhibition by two white people who lived a privileged life? I’m not at all saying there isn’t. I think art in all its forms is essential to human life and flourishing. But I wonder if we need to do more interrogating choices and standards. I wonder how you think this exhibition can speak into the time we’re living in, pandemic, revolution, and all.

CR: This opens onto the big question: What can art do? In particular, what can painting do? It was striking, talking to artists and art teachers of Warren’s generation, how many of them mentioned casually that paintings like his don’t get made anymore, and won’t get made in the future because the art world and, thus, the art schools have shifted so completely to the digital and the instantaneous. Pixels and computer programs have replaced time-consuming projects of learning about and manipulating physical media.

So what these paintings can do now is slow us down. I think that’s what you say, Julia, about what poetry can do, too. Together the paintings and poems maybe can offer an alternative to today’s culture of rapid-response virtuality. I’d like to think this is more than a you-deserve-a-break-today temporary reprieve. Rather it’s a fundamental reorientation of our experience, away from screens constantly competing for our attention and demanding our response, and toward slower cycles of the day, of the seasons, of a lifetime. Those cycles are no less important than news-and-entertainment cycles. Indeed, if we were more thoughtful about those cycles, maybe some of our news cycles would be would be less distressing.

JK: It’s also important to stress that the work of the Rohrers – and all art identified with Mennonite makers – is deeply influenced by conversations with others. Warren, for instance, studied art at Madison College – then a women’s education school [now James Madison University] – while also getting a degree in Bible at Eastern Mennonite College in the late 1940s. He applied himself to a lifelong investigation of art history from the West and East, ultimately embracing abstraction and identifying with the work of contemporary abstract painters such as the Canadian Agnes Martin and the African American Alma Thomas, among others. (I want to add, too, that his mother liked to draw birds and paint mottos, so folk art was there somewhere in the background, even as he sought other influences.)

CR: Yes, I think we can say that this exhibition, which we’ve been working on for a couple of years now, is not indifferent to race. My catalogue essay draws on Warren’s autobiographical statements to discusses his frequent allusions to seeing an abstract painting by the Chinese-French modernist Zao Wou-Ki and to the impact that painting made on his early development. Another of the catalogue essays, by Jonathan Walz, a curator in Georgia, compares Warren Rohrer’s approach to abstraction with that of Alma Thomas, an African-American painter whose work he admired. Walz observes that both artists came from backgrounds that excluded them in different ways from the art world, made their careers in cities other than New York, and forged painting styles that engaged the dynamics of colored mark-making in ways that don’t look like the work of New York artists who were their contemporaries, but that can appear in some paintings similar to each other. Jonathan’s essay uses the metaphor of the gleaners – and a famous painting of that title by the 19th-century French painter Jean-François Millet – to think about the idea of people on the margins making use of what the mainstream has left behind. This kind of search for commonality in what might be thought of as the quiet moments after the reaper has passed seems like it might relate to the idea of seeking for ways of being–and being together–on the margins.

ML: Since this is for a publication called “Mennonite” Life: What can Mennonites, in particular, learn/take away from this exhibit?

JK: I dislike (and can’t resist) making broad generalizations about groups. Yet if anything these days of protests show us, it’s that we must stop making generalizations. Nevertheless, I will point to Mennonite values as expressed in cultural products like our beloved cookbooks. The titles More-with-Less, Extending the Table and Simply in Season suggest the collective ideals of thrift and stewardship, inclusion and justice, simplicity and environmentalism. Sometimes it’s been hard for fine artists (not artisans) to find a place in that ethic of material, practical piety – and this is among the most dogmatically progressive groups.

And then there are the plainer groups. Because Anabaptists are diverse in many ways, there will always be aspiring artists like Douglas Witmer – who wrote a moving essay about Warren’s mentorship for our catalogue – for whom figures like Warren and Jane will be essential and emancipatory, as they were for me. Our exhibitions and catalogue engage respectfully with Mennonite experience in the 20th century in the United States as we consider the work of two individuals who were thoughtful in retaining the best of their traditional upbringing while shedding those elements that impeded their creative spirits. They both looked at the land, at traditional craft work, and at the past and made lives of deep commitment in the world. When has paying that kind of attention been more important – for anyone?

CR: Yes, and maybe this comes back to the earlier question about privilege. There are different kinds of privilege and different kinds struggles with constraints. On one hand, it’s a privilege to be rooted in a form of community that is itself rooted in tradition and rooted in a particular place. On the other hand, those forms of rootedness can easily become constraints. Both Warren and Jane Rohrer negotiated what it means to go away – physically, spiritually, intellectually – and how to return on their own terms. I think many people – not just Mennonites – can identify with that struggle, but it may have particular relevance for some Mennonite audiences.

Both Warren and Jane found ways to engage the values and labor of Pennsylvania agricultural life in their work. Our exhibition borrows from local institutions and from the Rohrer’s own collection of Amish quilts, painted Pennsylvania Dutch furniture, sponge-painted pottery and fanciful wooden objects (we have an amazing rocking horse from the Landis Valley Village and Farm Museum) in order to allow visitors to see the kinds of things that they were looking at and thinking about. And there are essays in the catalogue that address the Rohrers’ relationship to their background and contexts in their own words.

JK: As for the Mennonites – and here I mean the global minority that comes from European ancestry – it seems that those of us in the United States with Swiss origins have been very good at telling our religious and theological history, not as good at making and claiming contributions to broader culture – in contrast, say, to the Mennonites of Netherlandish and North German origins, especially those in Canada. This book appreciates and articulates the contributions of two 20th-century artists from (Old) Mennonite backgrounds. It includes essays by scholars and artists from both non-Mennonite and Mennonite backgrounds. (In addition to my essay about Jane’s poetry, painter Douglas Witmer writes about Warren’s influence on his own career, and public historian Janneken Smucker discusses the Rohrers’ early involvement in Amish quilt collecting and the influence of quilts on his painting process.) My hope is that this project will ensure that the work of Jane and Warren Rohrer maintains a place in the memory of some parts of the Mennonite subculture – in addition providing a deeper context for the artistic accomplishments they have contributed to the wider world.