“Where he got his material on us”: C.H. Wedel reviews Theodor Fontane’s Quitt

Theodor Fontane, who lived from 1819 to 1898, is widely regarded as the most important German novelist between Johann Wolfgang Goethe and Thomas Mann, the winner of the 1929 Nobel Prize for Literature. Since 1935 there has been an archive, now in Potsdam, devoted exclusively to Fontane and, since 1965, a journal, Fontane Blätter, dedicated to his life and literary output.[1] Günter Grass, the 1999 Nobel literature laureate, used Fontane’s novels and archive as the background and setting for his 1995 novel Too Far Afield, which dealt with German unification after the fall of the Berlin wall.

This prominent German author has a unique connection to Bethel College that only recently has been fully understood. His 1891 novel Quitt followed Lehnert Menz, whose conflict with narrow Prussian authoritarianism in the first half of the novel leads him to flee Germany and in the second half to seek employment with a Mennonite family in Indian Territory, now Oklahoma. Here Lehnert finds salvation, acceptance and a potential bride in Ruth Hornbostel, the daughter of the Mennonite elder Obadiah Hornbostel, before he dies in tragic circumstances. In the novel, Ruth spent some time at the Mennonite school in Halstead, the forerunner of Bethel College, and is therefore now listed as an honorary, if fictitious, alumna in the college’s alumni directory.

Many critics have harshly criticized Fontane’s America as unrealistic and have not known what to make of his Mennonites, while a few have argued he researched and used Mennonites in order to criticize Prussian militarism.[2] This article examines a recently discovered three-part review of Quitt written by Bethel’s first president, Cornelius Heinrich Wedel, and documents Wedel’s role, along with David Goerz, in producing the Mennonite material that Fontane used in his research for the novel. Wedel ultimately reviews Quitt without knowing that Fontane had been reading material produced by Kansas Mennonites, a hidden transatlantic cycle of literary production and review. Wedel’s three reviews appear here for the first time in English, followed by a more detailed analysis of why Wedel hated a novel that I admire.[3]

Bethel College Monthly (Monatsblätter aus Bethel College) 8, no. 5 (May 1903): 52-53.

A Novel about Prussian Mennonites

Not even the Prussian Mennonites could avoid being mentioned in fictional literature. The famous poet [Ernst] v. Wildenbruch wrote a play about them that is a monument to avoiding any hint of historical accuracy, a play that is known everywhere but in our country. An even worse distortion of their essential characteristics, that is, of their religious beliefs, has been created in one of the latest novels by poet and essayist Theodor Fontane. Fontane is otherwise one of the most reliable authors of the modern age. He has written grippingly about English folklife, but especially about the daily life and activities of the folk who populate his native Brandenburg. He was born in 1819 and for a time was the Secretary of the Berlin Academy of Sciences, in short has had a successful career. Adolf Bartel wrote of him in Sketches of Contemporary German Literature (Skizze der deutschen Literatur der Gegenwart) that he rejected the fashion of cloning stories and sought out instead original material from real life, even if it was not always attractive or delightful. Thus, he paid homage to naturalism and while hunting for any possible new material he must have ran across our Mennonites. He had enough faith in his knowledge and judgment to offer the German-language reader a description of their characteristics.

He did not lead his audience to the banks of the Vistula River,[4] however, but to America and here to Indian Territory. According to his story [52], a settlement of Prussian Mennonites named Nogat[5]-Honor (Ehre) nestles in a wide valley between the Shawnee Hills in the east and the Ozark Mountains in the west. A string of farms was built along a foaming creek. Palm and elm trees surround the houses. A few miles to the east of the village lies Darlington Station on the Texas-Kansas-Missouri railroad line coming up from Galveston. To the west are only miles of pine and cypress trees stretching across flat land to the mountains, land inhabited by the Cherokee and Arapahoe Indian tribes and where four Mennonite missionaries, Krehbiel, Nickel, Penner and Anthony Shelly work. In the village of Nogat-Honor the most impressive farm belongs to Obadiah Hornbostel, the elder of the congregation. His house has two stories, with the living space and bedrooms upstairs and a large meeting room downstairs. Obadiah has been married three times. The children from his first wife have returned to Prussia since they did not like it here. He lived in Dakota for years, from there he moved south; two children, Toby and Ruth, brighten his twilight years. For being seventy-three years old, however, he is still in quite fit. The other inhabitants of his house are a colorful bunch. They remind a stranger of a cage in San Francisco that housed a snake, a bird, and a cat all living peacefully together under a label, “A Happy Family.” There was an elderly maid, Maruschka, Polish and Catholic, a Lutheran Kaulbars family from the Nogat area of Prussia who hold the military in the highest regard, and a worldly-wise Frenchman who has struck the God proclaimed by priests from his catechism yet nonetheless observes the religious exercises with the interest of a philosopher of real life.

Elderly Obadiah remains the driving force of the house, who accepts any eccentric who is willing to get along peacefully with him and the house rules. He believes that God has led each household member to him and that even the mocking Frenchman will have an experience of grace. On the whole, he appears as a clever church ruler well able to calculate his own advantages, a “High Priest” of Nogat-Honor. He had a well-developed sense for a finely laden table and did not mind a bit when chickens and geese were hunted and plucked for Christmas. He knew how to increase his own fortune. Kaulbars held forth about him that, “sure, he is one of the best, but listen, it is also true, he knows exactly where Bartel gets his fermented cider and that asparagus tips taste better than the stems and he has money in the bank in Denver and in Galveston and in Amsterdam and other places yet too. When one is always acting like the Christmas story was just for him, he doesn’t have to keep the books like a bank director does.” Obadiah himself described his situation like this, “You can make yourself the most useful by working, clearing out both the forest and paganism and replacing it with faith in Jesus Christ our Savior. Yes, one serves Him best by keeping order and working and not letting things go to pot.”

At the start of the service, Obadiah said, “Let us pray. Prayer sanctifies us and sets our souls free. Prayer makes every day a holiday. I would like to apply Benjamin Franklin’s comments on moderation to piety instead: it puts coal on the fire, flour in the barrel, money in the wallet, and credit with the world, satisfaction in the home, clothes for the children, reason in the brain, and all of life in its proper stations. This is miracle wrought by piety and prayer is our help and aid.”

Thus, and with additional comments one can read Fontane fantasizing about our Mennonite rural pastor. The fact that he has not studied this setting like he did his native land before writing his Ramblings through Brandenburg is readily apparent. He clearly does not know the topography of the American part of his story. The malice in his characterization of a Mennonite elder must be clear to any reader who stops to think about it. We will return to his novel in our next issue.

w.

This book, which has almost 400 pages, can be requested from the editor. $1.25 bound, ten cents extra for shipping.

Bethel College Monthly (Monatsblätter aus Bethel College) 8, no. 6 (June 1903): 64-65.

A Caricature of Mennonite Indian Missions

The most infuriating caricature was developed by Fontane in the novel mentioned in the last issue, making one ask how such a reputable author could slop such stuff together. He has Lehnert, a German immigrant, join the household of Elder Obadiah Hornbostel and observe all the religious customs of the congregation and the mission. Lehnert notes that in September, when the grain is hauled away by rail or loaded onto barges to be shipped down the Red River, there are additional church duties for Obadiah. There are various conferences that Mennonites from Nogat-Honor, Kansas, and Dakota hold. There is a constant coming and going that keeps the household on its toes. Finally, the elderly Obadiah travels to Halstead, Kansas, where his daughter Ruth had attended school, to discuss the approaching festivities. Lehnert finally asks the others in the household, especially the philosophical Frenchman, what it all means and what is happening. The short answer is, “It is washing time, Mister Lehnert, washing feet. And kettle drums and Gunpowder-Face, well you know him… and Obadiah preaching; and plenty of people.” This answer leaves Lehnert no wiser than before and so the Frenchman gives a longer explanation. The end of September is the most important time at Nogat-Honor. All the Mennonites within fifty miles come together there and there are big doings in the meeting room. It is not exactly civilized, but since one cannot have a comedy, this Holy Sabbath celebration is the next best thing the area has to offer for entertainment. It starts with a kind of warmup, that is with foot washing where Obadiah takes on the role of the savior. He does a good job, but it is all out of date by a hundred years. This ceremony is at night. The next day is the high point of the program. The tabernacle is so crowded that an apple could not find its way to the ground. If there are any gaps, they stuff a couple of Indians in there. Finally, Obadiah appears and says the prayer. Then or on the next day he baptizes the candidates, which seldom include a white skin. Later on, Ruth sings, which is always the best thing, and then the choir of Arapahoe and Cherokee children join in. That makes a tremendous noise, especially when Gunpowder-Face accompanies them with his drum from Mexico. He looks like a Mexican high priest and completely overshadows Obadiah.

Sure enough, a few days later, Nogat-Honor is overflowing with Mennonites and Indians. The prayer hall is decked out with garlands and flowers. Ruth is up on the balcony with the other Mennonite girls in order to lead the singing. They are surrounded by numerous Indian children, one of whom, a pretty girl, holds a banner that depicts Christ enthroned on clouds. The Frenchman made this banner and made Christ look more like a Judas. Gunpowder Face was standing with them along with his drum and two kettle drums. In front of the balcony stood the altar. At the front of the hall the Arapahos who were going to be baptized were seated, along with their sponsors, the missionaries and teachers who led the work of converting them. One of them was clearly an Englishman, with a delicate hound face. The others were all Germans, which you could tell from their square heads and stereotypical German names. At the last Obadiah appeared, prayed, preached a sermon about the depravity of war, and performed the ceremony. Ruth played the organ and she and the children sang. Gunpowder-Face, however, beamed as he beat his heathen instrument, and thus, richly blessed, the festivities concluded.

This is the depiction of a Mennonite mission festival among Indians according to the expertise of a famous German writer. Luther remarked in 1518 in Augsburg concerning Cardinal Cajetan that he knew as much about the Bible as a donkey did about playing the harp. The same could be said about Fontane’s ability to describe mission activities.

w.

Bethel College Monthly (Monatsblätter aus Bethel College) 8, no. 8 (August 1903): 87-8.

The Basic Premise of Quitt

The premise of the novel by Fontane that we have discussed in a couple of issues already needs to be outlined briefly before we lay this work aside. We will not occupy ourselves with it again any time soon. Today in a novel one in general attempts to provide an artistic depiction of an idea or element of contemporary cultural life. One can imagine how easily in this kind of literature godlessness and immorality become a focus. The dark side of ordinary life is displayed or the modern doubt of anything holy is investigated and in the process the disposition of the reader is affected, often without the reader even noticing. Thus, every thoughtful, and especially every Christian, reader will be highly attentive in order not to acquire dangerous material that might quickly have to be pitched into the fire. Much can only be read at best with caution and only as a mirror into what the so-called “educated world” is embracing by noting the ideas and perspectives presented.

Fontane’s Quitt fits well into this kind of fictional literature. We would cast it far aside if his depiction of Mennonites did not seem important to us. It seems doubtful, however, to what extent he was really interested in informing readers on this particular point. We would really like to know where he got his material on us. Did he run into our Christian Covenant Messenger with its missionary reports somewhere? Or did letters from a German immigrant soldier serving at Fort Reno who wrote home somehow end up in his hands? He died in 1893,[6] so we cannot ask him. To us it seems that his reporting on Mennonites is a welcomed side story to his main tale, providing an important context for his protagonist and the basic premise of his work. Quitt is a novel pursuing a current trend, describing an ethical teaching that is so widespread in the modern world and so easily gains access among Christians that we wish to name and highlight it here.

The protagonist is a certain Lehnert, who Fontane has grow up poor in Silesia. Nonetheless he has a lot of self-confidence and in the war [with France in 1870] his bravery stands out, so that he would have been awarded the Iron Cross if only his neighbor, the game warden Opitz, had not managed to downplay his achievements in the eyes of their commander. Lehnert cannot forget this slight and the tension between the two becomes increasingly ugly. With fine craftsmanship the author depicts the actions and reactions of both in their lower-middle class setting as well as their thoughts and their outbursts about each other. It is obvious he is in his element here; he is writing about “what he knows.” Lehnert’s growing hatred of Opitz progresses in a way that seems psychologically natural to the point of plotting his murder. He comes to see the black deed as his preordained fate. Opitz is assassinated in cold blood, Lehnert, however, miraculously escapes to America, following the furies of his guilty conscience. For six years he crosses the north and west of the enormous country until he finds a type of asylum with the Mennonite elder Obadiah Hornbostel in Indian territory, where he finally comes to understand his own internal condition.

In conversations with the family and under the influence of the Mennonite perspectives shared there and in the church services, specifically the teaching of non-resistance, he encounters three important factors. In Ruth, the daughter of Obadiah, he discovers the grandeur of a noble feminine soul, in the rite of baptism, the possibility of an internal transformation, and in the talk and sermons of Obadiah the damnation of murder and necessity of atoning the blasphemous deed. Fontane deals with the first two points quickly. Lehnert falls in love with Ruth and is so transfixed by her singing that he collapses unconscious. With Ruth’s encouragement he regains consciousness, confesses his past to Obadiah, and through baptism joins the Mennonite congregation. That is his conversion experience. Once his love of Ruth has been proven by an act of heroism, winning her hand seems to be just around the corner. But before he can organize that next step, her brother gets lost in the mountains and Lehnert in his haste to find him falls so awkwardly from a cliff that he dies alone in the wilderness before help arrives. The search party finds him dead, in his hands a note on which he wrote in his own blood, “Our Father, who is in heaven, … And forgive us our debt… And you, Son and Savior, who died for us, intercede for me and save me… And forgive us our debt… I hope: paid up (quitt).”

This finale ruins our enjoyment of the novel. Fontane leaves no doubt how we are to understand this “paid up.” He has Obadiah write a letter to the local authorities of Lehnert’s village in Silesia, informing them of what happened, how he became a favorite in his household, and how he died while trying to rescue his son. His repentance had reconciled his debt, Obadiah wrote at the end of his letter. Saving oneself, reconciling one’s guilt by one’s own actions, by having a loving disposition, by sorrow and suffering over the done deed, yes, by offering his life to save an accident victim, this is the basic premise of the novel. A person’s own good deed will balance out his evil deed, so that he can write “paid up” on the bill himself. One cannot deny that the court of human judgment might make much of this process, but doesn’t Lehnert belong back in Silesia to receive his due for his deed? Where would we find a Mennonite preacher who would let his daughter marry even a repentant murderer? And how decisively do all of our catechism books teach that it is not one’s own doing, but the blood of Jesus Christ that cleanses all sin! Making a Mennonite elder the carrier of the modern idea of humanity saving itself simply defames our position. As much as we emphasize practical Christianity and see the proof of our faith in a hard-working life and energetic interest in the less fortunate, these activities cannot be seen as repayment for any kind of crime. True Christianity does not acknowledge any saving of oneself. This idea blossoms rather in worldly thinking, even if it is otherwise quite noble. Goethe has the angels in Faust sing, “Whoever tries faithfully we can save,” and Auerbach prates about it in his novel On the Heights (Auf der Höhe). Fontane does the same in Quitt. Both as a work of art and in consideration of its ethical premise we must characterize the novel as unsuccessful. It does not inform us, it does not educate us, and for Mennonites who are so prominently featured here, it is a public insult.

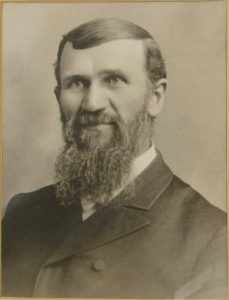

In 1903, five years after Theodor Fontane’s death, Wedel reviewed Quitt, the only review published outside Europe.[7] Before moving to North Newton, Kan., to take up the Bethel College presidency in the fall of 1893, Wedel had been teaching since 1890 at Halstead Seminary (Fortbildungsschule) 13 miles to the west.[8] Wedel’s extensive review was published over three issues of the Bethel College Journal (Monatsblätter aus Bethel College). In the long line of negative reviews and comments about Fontane’s lone fictional setting in America, this new Mennonite voice adds perhaps the most caustic comments. Given his own intimate knowledge of Mennonite mission work in Indian Territory, Wedel wondered how Fontane “could slop such stuff together,”[9] and implied the book might have to be pitched into the fire. Wedel’s ire focused on Fontane’s portrayal of the Mennonite elder Obadja (Obadiah) Hornbostel, his depiction of the baptism festival at Nogat-Honor, and what Wedel considered to be Fontane’s promotion of a modern and unchristian idea of self-redemption in the guise of Mennonite theology.

In addition to having been an instructor at Halstead, Wedel was also briefly a mission worker with the Mennonites among the very Native Americans Fontane described. Moreover, his close friend and associate, David Goerz, was the key editor or publisher both of the mission reports by Mennonites that eventually made their way to Fontane and of Wedel’s review itself. Thus, this review represents first the production of mission work reporting by Mennonites in the Great Plains of the United States, then its dissemination to Germany, its discovery and use by Fontane and, closing the loop, a review by the most important intellectual leader of the Mennonite community central to the message and setting of the book. The circulation of this colossal cycle, however, eluded Wedel and Goerz at the time and, in its entirety, scholars to this day.

Cornelius Heinrich Wedel

Understanding C.H. Wedel is one important place to begin unpacking this process. Besides serving as Bethel College’s first president, he was also an ordained Mennonite minister and leader of the congregation that became Bethel College Mennonite Church. Comparing his background to that of Obadiah Hornbostel, the Mennonite minister in Quitt, offers perspective on his negative review of the novel that focused on Mennonite aspects and not on depictions of geography, Native Americans, or American society, or on narrative deficiencies like most other critics. Wedel was born in 1860 in the Molotschna Mennonite Colony in Russia, today an area about 50 miles south of the Ukrainian city of Zaporizhzhia. His father, Cornelius P. Wedel, was a village schoolteacher. The family joined a large 1874 migration of Mennonites to Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota and Manitoba as they sought to avoid newly instituted military conscription. Their congregation in Russia, Alexanderwohl, split into two settlements in Kansas, one also named Alexanderwohl, 18 miles north of Newton, and another named Hoffungsau, 30 miles west of Alexanderwohl. Wedel’s family was part of the new Alexanderwohl congregation. Two years after arrival, at age 16, Wedel was teacher of a private German-language school held in one room of a farmhouse. During the four years he taught there he also taught himself English.

After taking a couple years to complete high school in towns nearby, in 1881 he departed for the Mennonite mission field at Darlington in Indian Territory which had only been established the year before. There he took up teaching Native American children. Two and a half months after his arrival, the main building burned down, killing all four of lead missionaries Samuel and Susanna Haury’s young children, Emil, Walter, Carl and Jennie (their 3-year-old Indian foster child). The reconstruction work that followed with its dust and physical strain were too much for Wedel, who suffered his whole life from weak eyes. He had to leave the mission and sought medical treatment in St. Louis. When he read Fontane’s depiction of Indian children and missionary work, he was thus able to make direct comparisons to the reality, an option not open to any other reviewer.[10]

Letter from H.R. Voth to David Goerz on mission letterhead (Mennonite Library & Archives)

Although he left the mission field, Wedel’s interest in missions remained. With the financial support of his home congregation, he next went to study at a Methodist school, McKendree College, now University, in Lebanon, Ill., only four miles west of Summerfield and about 30 miles east of St. Louis. First Mennonite Church in Summerfield, founded by Mennonite immigrants from the Palatinate who arrived in the 1850s and 1860s, was an important connection point for some Russian Mennonites arriving in the 1870s. The mission board meanwhile pressed him to return, but he instead, in 1883, arranged a temporary leave to protect his health and continue his education. That leave turned out to be permanent, but he became a mission board member in 1902 and served until his death in 1910. From 1884 to 1887 he next studied at German Theological School, now Bloomfield College, in Bloomfield, N.J., a Presbyterian school with German Reformed connections. Here he was deeply impacted by the German Idealism of Professor George Carl Seibert, who convinced Wedel to stay on the year after his graduation as an instructor. In 1888 he faced offers from his home Alexanderwohl community to teach at their rural Emmathal school, the Mennonite school in Halstead, founded in 1883, or at a school in Chicago, or to continue in his position at Bloomfield. Following a third year of teaching at Bloomfield, in 1890 a cycle of outside offers repeated, including from Halstead, plus one from a new Mennonite school just north of Newton, Bethel College, and a one-year offer to return to the mission field in Indian Territory. Wedel accepted the Halstead offer, working there until finally moving to Bethel in 1893. He thus taught at the same school that Fontane’s characters Ruth Hornbostel and Shortarm attended, a school that was in fact open to Native Americans from the very beginning, although most attended an Industrial School designed for vocational training, run by Christian Krehbiel, also in Halstead.[11]

Letter from H.R. Voth to David Goerz on Halstead School letterhead (MLA)

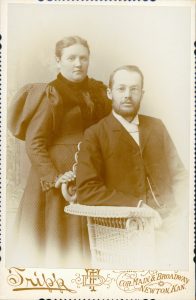

Mission and church work remained important interests for Wedel during this time. Home on summer vacation, he traveled to visit Indian territory on August 26, 1887, where he became engaged to a mission worker, Susanna Richert, on Sept. 7. She remained on the mission field until Wedel committed to moving back to Kansas. Her refusal to move to New Jersey played a major role in his eventual permanent return in the summer of 1890. She was also from the Alexanderwohl congregation, where Wedel, on Aug. 17, 1890, was ordained as a minister. Now settled at Halstead, on March 30, 1891, he was able to get married. His new father-in-law, Heinrich Richert, was a minister in the Alexanderwohl congregation and had been a member of the board that oversaw the mission work. Richert was also on a special committee that dealt with tensions between the older Halstead school and the new Bethel College. Officially Halstead was to serve as a feeder school for Bethel, but in fact Bethel ended up replacing it. Wedel had married into an important Mennonite family that provided crucial support for his work.

Cornelius and Susanna Wedel, ca. 1905

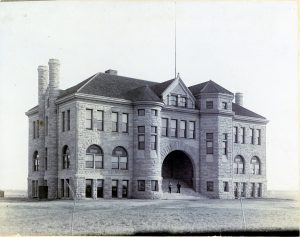

In 1893 the Halstead school closed, and all the buildings were moved to Bethel, which had taken six years to raise the money needed to build its first permanent building.

The Ad Building, where Wedel’s review was written, ca. 1894

Wedel became Bethel’s founding president and moved into an apartment in the new building. In addition to teaching Bible, serving as pastor of a new college church, and running, publicizing and fundraising for the institution, Wedel also created portions of the curriculum by writing four volumes on Mennonite history and additional volumes on the Bible and Mennonite theology. His theological training and writing explain why his objections to Quitt focused on Mennonite theology and culture.[12]

Wedel’s work to publicize the school had to fit in around his other responsibilities. As he noted in his diary on Feb. 7, 1903, “off and on I am getting articles ready for the fourth issue of our school papers.”[13] His Quitt series started in the fifth issue, so were written shortly thereafter. Wedel’s three-part review was a small portion of the 45 articles he wrote for publication that year in the Monatsblätter aus Bethel College. Other articles ranged from Russian Mennonite developments to church history and educational matters.[14]

His original thought on Quitt was, “We would cast it far aside if his depiction of Mennonites did not seem important to us.” The next question was, “We would really like to know where he got his material on us. Did he run into our Christian Covenant Messenger with its missionary reports somewhere? Or did letters from a German immigrant soldier serving at Fort Reno who wrote home somehow end up in his hands?”[15]

Fontane scholarship has known for a long time that Fontane indeed acquired Mennonite mission reports.[16] On closer examination, however, it turns out that all of Fontane’s information on Mennonite mission work came one way or another from the publicity work of David Goerz. Thus, it is ironic that Wedel could not decipher this puzzle of Fontane’s Mennonite sources since Goerz was his good friend and the business manager of Bethel College.

David Goerz

Like Wedel, Goerz was born in Russia, in 1849 in Berdjansk on the Black Sea, the town that served as the port for the Molotschna Mennonite colony. A gifted student, at age 18 he was hired as a tutor for the children of Cornelius Jansen, a grain merchant who had moved to Russia in 1856 from the Mennonite settlements in the Vistula Delta. Jansen later became a main proponent of Mennonite emigration out of Russia. Goerz’s friend, Bernhard Warkentin, visited America already in 1872, staying at Summerfield, Ill., with Christian Krehbiel, a recent immigrant from the Palatinate who later spearheaded the Mennonite settlement at Halstead and ran the vocational school for Native American children. Warkentin’s letters to Goerz about America prompted Goerz to emigrate already in 1873 in advance of the large-scale migration the following year. Goerz taught school in Summerfield for two years before moving to Halstead in 1875 with Krehbiel, Warkentin and others from Summerfield arriving at different times.

In Halstead, Goerz became a key leader in Mennonite education endeavors. In 1877 he organized the first Mennonite Teachers’ Conference in Kansas, a group that advocated strongly for a Mennonite school for teacher training. In 1882 he was on the committee that formed the Emmathal school near the Alexanderwohl church. He was secretary of the group that in 1883 started the school in Halstead, to which Warkentin and Goerz gave the first donations. He helped recruit his friend C.H. Wedel to teach there in 1890. An offer of money and land from the city of Newton led to the founding of a new school near there, Bethel College, in 1887. Goerz was the driving force behind this school as well and became its first business manager under the new president, Wedel, when the school finally opened in 1893.[17]

Goerz also remained active in immigration activities in Halstead, serving as secretary of the Mennonite Board of Guardians set up to assist poor Mennonites with migration expenses. Crucially his immigration involvements came to including newspaper publishing. He launched a newspaper, To Home (Zur Heimath), started already in 1875 in Summerfield that was distributed free to immigrants from Russia by the board. A notice in the main Mennonite newspaper in Germany, the Mennonite Journal (Mennonitische Blätter), announced the new paper. They noted they had received many free copies and were including them with their own edition “as long as supplies last.” Goerz was named as the editor in this article and the board was explained to German readers, stressing its function of protecting immigrants from unscrupulous operators by providing information on steamer and railroad fees and an extensive listing of names and addresses of where Mennonites had settled. “That way the next round of settlers knows where to go if they want to join relatives or neighbors who have gone ahead.”[18]

In 1877 Goerz dropped the mission report portion of his newspaper in order to start a new paper that would focus exclusively on mission work. News from Heathen Lands (Nachrichten aus der Heidenwelt) was still published by his Western Publishing Company in Halstead although there was a different editor, C.J. van der Smissen. In 1882 both papers were merged with an eastern Mennonite paper, Mennonite Peace Messenger (Mennonitische Friedesbote), to create the Christian Covenant Messenger (Christlicher Bundesbote). Goerz was the first editor of this paper, serving until 1885. Fontane got in touch with Heinrich Gottlieb Mannhardt, the Mennonite pastor of the Danzig Mennonite Church, seeking mission reports sometime after Aug. 2, 1885, when he had written his son Friedrich to thank him for finding that connection. Fontane developed his conception of the novel in 1885 and wrote the first draft in 1886. Whether Fontane was given copies of Mennonite Journal or the south German Mennonite paper, Mennonite Congregational Newspaper (Gemeindeblatt der Mennoniten), they were simply reprinting material from papers edited or published by Goerz, making him a key, but unknown, Fontane informant.[19]

David Goerz, ca. 1895

The work of publishing a journal for the college was authorized by the board of directors, which at its November meeting in 1895 made Goerz the editor of the new School and College Journal with the first issue appearing in January 1896. In 1903 the paper was split into separate English and German versions, with Gustav Haury editing the English and Goerz the German, named Bethel College Monthly (Monatsblätter aus Bethel College).

The German-language publications of Goerz kept Bethel College and its Mennonite community connected to Prussian and Russian communities, with reporting and letters going back and forth both ways. For example, in January 1882 a letter was sent to Goerz from Gnadenfeld, Molotschna Colony, Russia, with a list of local subscribers to his papers To Home and News from Heathen Lands along with a complaint that two subscribers had not gotten their papers. Two months later a letter was sent by Pastor Leonhard Stobbe in Montau, Prussia, asking for assistance for a poor Mennonite family from his congregation who wanted to emigrate to Kansas. The May 1903 issue of the Bethel College Monthly, in which the first portion of Wedel’s review appeared, reprinted portions of letters from readers in Prussia and Russia. A pastor from Prussia asked to have his subscription extended through 1904 and noted, “This will strengthen the band of brotherly love that binds us together.” An elder from Russia sent in a long list of subscribers from his congregation. Even this cursory look at Goerz’s publications shows the key role he played in keeping a transnational Mennonite community connected, that Fontane was then able to tap into and use as a transnational German community for his purposes in Quitt. The house Goerz built on the college campus serves Bethel College today as its presidential residence. Goerz’s retirement in 1910 due to poor health and death in 1914 robbed the college of a person with the drive and personal connections to keep the bonds of brotherly love strong and Bethel’s prominence among Mennonites in Europe faded away.[20]

Goerz House, ca. 1905

Obadiah Hornbostel – A Disparaging Distortion

Wedel opened the first segment of his review by noting that Mennonites had been used to illustrate ideas in German culture before, citing the play The Mennonite (Der Menonit) [sic] by Ernst von Wildenbruch, which, he added, fortunately was not well known in America since it painted Mennonites is such a negative light. Fontane’s portrayal, Wedel thought, was even worse, especially concerning Obadiah. As an ordained minister and church leader, Wedel may well have been particularly sensitive to Fontane’s distortions here. Mennonites in North America, who for the most part maintained their absolute refusal to serve in the military, were used to being branded as traitors as von Wildenbruch had done. Presumably Wedel was therefore not bothered by the play although it faced fierce opposition from German Mennonites, who had all agreed to join the army by the 1880s, and unsuccessfully protested its staging in Berlin in 1888 all the way up to Emperor Frederick III. Thus, the location and theological positioning of Mennonites themselves at the time mattered a great deal in how Quitt was received. Ernst Correll, writing a decade after Wedel for the German-language Mennonite Encyclopedia (Mennonitisches Lexikon), found Fontane’s image of Mennonites to be “authentic and truthful,” in contrast to von Wildenbruch’s.[21]

Wedel’s review began with a short and incomplete overview of Fontane’s career and a brief summary of the second part of the novel set in Indian territory. In listing the names of the missionaries in the novel, he corrected the spelling for Anthony Shelly, instead of Fontane’s Shelley, since he knew the man personally. Shelly was originally from Pennsylvania but taught at the Halstead school 1884-86. Wedel recorded spending time with him in 1896 at a national church meeting. Fontane, however, referred in his book A Summer in London (Ein Sommer in London) to the poet Shelley several times, so perhaps he assumed that was the proper English spelling.[22]

In Wedel’s estimation the community leader was presented as “a clever church ruler well able to calculate his own advantages, a ‘High Priest’ of Nogat-Ehre. […] He knew how to increase his own fortune.” Wedel himself had to delay marriage for years due in part to a lack of money. He made approximately $600 a year teaching both in New Jersey and Halstead. In general, rural Mennonite pastors were self-supporting farmers, as Fontane portrayed Obadiah. But as spiritual leaders they were also obligated to care for the poor in their congregation or broader community, as the example of the Mennonite Board of Guardians showed. Certainly, wealthy farmers were overrepresented among leadership, but they were expected to give up a lot of time without compensation to serve the church. Wedel was paid for his teaching, but not for his pastoring. Wedel seems highly offended at the insinuation that Mennonite pastors were somehow particularly attached to material wealth.[23]

Obadiah’s poor theology was equally appalling for Wedel. His lengthy commentary on piety as a path to wealth continued in the same vein. “I would like to apply Benjamin Franklin’s comments on moderation to piety instead: it puts coal on the fire, flour in the barrel, money in the wallet, and credit with the world.” For Wedel, Fontane had constructed a phantasy concerning a rural Mennonite pastor. His careful studies of the Mark Brandenburg, some of Fontane’s most loved writing, had not been replicated here. “He clearly does not know the topography of the American part of his story,” was Wedel’s only commentary on the novel’s geography. For readers of the college’s paper, it would be clear that Fontane’s image of a rural Mennonite pastor was “a disparaging distortion.”[24]

Nonetheless the review ended with an offer, not subsequently repeated, that one could order the book from the editor for $1.25 plus a dime for shipping. Unfortunately, no copy from then remains in the college library today.

The Mennonites’ Mission to Indians – A Most Infuriating Caricature

Perhaps Wedel’s many responsibilities got away from him in the time he prepared this review, which is primarily a heavily edited version of the baptism ceremony at Nogat-Ehre taken from Chapter 24. He noted that Ruth had studied at Halstead and that Obadiah visited there in preparation for the event. Then both Toto and L’Hermite are quoted trying to explain it, understandably not giving religious explanations. Even when the narrator’s voice resumes in the review, Wedel included the spectacle and not the religious aspects of the gathering. The contents of the sermon, for example, and Lehnert’s conversion are omitted while the offensive drums of Gunpowder-Face are highlighted. For early Mennonite missionaries, drums were still considered something heathen, a label Wedel adds here in his editing of Fontane’s account. The first Mennonite missionary to Native Americans, Samuel S. Haury, on his initial encounter with their religious rituals that included drumming, thought that it was “guided by Satan.” Topping off a solemn baptism with such commotion led Wedel to this outburst in conclusion. “Luther remarked in 1518 in Augsburg concerning Cardinal Cajetan that he knew as much about the Bible as a donkey did about playing the harp. The same could be said about Fontane’s ability to describe mission activities.”[25]

Saving Yourself

Wedel opened his third and final review segment with a brief comment on literary theory. “Today in a novel one in general attempts to provide an artistic depiction of an idea or element of contemporary cultural life.” He goes on to warn his largely rural and self-educated Mennonite readership that a Christian reader needs to take care not to inadvertently acquire spiritually dangerous material, “that might quickly have to be pitched into the fire.” One is reading a mirror image of what the educated world thinks about the issue at hand. Quitt would have been in this category of works to discard if not for its Mennonite content, leading Wedel to speculate, as we have seen, on where Fontane got his Mennonite material.[26]

Wedel identified the protagonist Lehnert Merz as the carrier of this main idea. He was full of praise, like many other critics, of Fontane’s description of the struggle between Opitz and Lehnert in the first half of the novel. Once Lehnert arrived among the Mennonites, Wedel credited his conversion to the Mennonite teaching of non-resistance along with Ruth, who represents “the grandeur of a noble feminine soul,” the possibility of inner change represented by baptism, and the preaching of Obadiah on the evil of murder and the need for repentance.[27]

The final act, however, completely ruined the novel for Wedel. The note that Lehnert wrote in his own blood as he lay dying and the letter that Obadiah wrote back to village officials in Silesia made Wedel think that “his repentance had reconciled his debt […] Saving oneself.” As Wedel noted, Mennonite teaching had always been that the blood of Jesus Christ was the only path to cleansing sin. And a Mennonite elder marrying his daughter off to a murderer? Finally, putting the modern idea of redeeming oneself into the mouth of an elder simply “defames our position.” Wedel ended by noting that such ideas were good enough for Goethe in Faust or for Auerbach in On the Heights (Auf der Höhe), but for Mennonites it constituted “a public insult.”[28]

How might we interpret Wedel’s disdain for a novel that otherwise puts Mennonites and one of their central doctrines, non-resistance, in such favorable light? Especially since a minority of critics over the years have highlighted the critique of militarism and the need for peace and tolerance as the main, and politically subversive, idea in Quitt?[29] One possibility would be to note that the traditional Mennonite approach to peace drew directly from the Bible and the life and teachings of Jesus and not from social or political considerations. Therefore, Fontane’s watering down of Mennonite spiritual life to be one of ritual and cost/benefit analysis while highlighting the social benefits of peace might have put Wedel off. He allowed in his conclusion that Mennonites have always valued practical, active Christianity as a sign of true faith, but have strictly avoided thinking of such actions as payment for sin or works that accrue righteousness. Thus, for Wedel, just promoting peace and forgiveness was not enough, the reason behind it had to be authentic, meaning for Mennonites connected to Jesus and the Bible.[30]

It would be a mistake, however, to draw too sharp of a distinction between biblical and worldly peace in Wedel’s thinking. Immediately preceding his second segment on Quitt was his article “The Idea of Peace in the Social and Political Arena” (Die Friedensidee auf sozial-politischem Gebiet).[31] Launching his analysis with the Hague Peace Conference of 1899 convened by Russian Tsar Nicolaus II, he referred to secular peace projects ranging from William Penn’s Quaker colony, Rousseau’s vision of primitive society, Kant’s Eternal Peace (Zum ewigen Frieden), the British peace society and the activities of Richard Cobden, and efforts to establish an international system of arbitration. Additional examples that would have been, like the Hague convention, after Fontane’s death, included Bertha von Suttner’s Weapons Down (Die Waffen Nieder), Rudolf Virchow’s quote, “Disarmament or self-destruction, that is the dilemma of Europe’s nations,” Tolstoy, and Otto Umfrid. All of this peace work was praised and highly recommended to readers. It is notable that Fontane engaged in none of this type of activity, which might have been too explosive in his milieu and for his readership in any case. He preferred literary subtlety to open advocacy but was perhaps too subtle for Wedel and most other critics.

A final possible source of anxiety for Wedel concerning Quitt was that such modern ideas in Mennonite preachers or teachers’ heads was simply too dangerous for his institution and his church. The modernist-fundamentalist conflicts in American Protestantism were well underway by this point and Wedel needed to avoid them. He had encountered modern literary criticism of the Bible in his studies in Bloomfield and noted, “I myself fumbled about a bit with this burst of new knowledge, especially about the Old Testament. Now everything seems to become shaky.” The very first issue of the School and College Journal provoked an outpouring of letters to the editor questioning many aspects of the school’s approach and operations. The paper served as a kind of safety valve to air grievances, hopefully without things getting out of hand. The lid did not come off until 1916, six years after Wedel’s death, in the notorious “Daniel Explosion” that saw two Bethel professors, one modernist and one fundamentalist, attacking each other publicly in chapel over the proper interpretation of the Old Testament book of Daniel. In this context warm praise from Wedel for a theologically lukewarm, materialistic Mennonite preacher who just happened to talk about peace would have been politically risky and in any case did not line up with either Wedel’s heart or head. [32]

Cornelius H. Wedel together with David Goerz shaped the Mennonite mission and publishing efforts in Kansas and Indian Territory that came to Fontane’s attention just as he was developing the manuscript for Quitt. Both Wedel and Fontane were interested in critiquing militarism and in working for peace in different ways. But neither could fully appreciate the approach or contributions of the other. They remain nonetheless linked together in one of the most unusual rounds of source creation and publication review in Fontane’s world.

[1] See https://www.fontanearchiv.de

[2] These details are available in Mark Jantzen, “‘Wo liegt das Glück?’ Reflections on America and Mennonites as Symbols and Setting in Quitt,” Fontane Blätter, 104 (2017): 91-116. Some of Fontane’s connections to Bethel and Native Americans were detailed in “The Darlington Mission in Theodor Fontane’s Novel Quitt,” Mennonite Life 61 no. 2 (June 2006): https://mla.bethelks.edu/ml-archive/2006June/jantzen.php

[3] My thanks to John D. Thiesen, archivist and co-director of libraries at Mennonite Library and Archives and Bethel College, for bringing Wedel’s review of Quitt to my attention.

[4] Now in Poland, then the Vistula delta region was home to the largest settlement of Mennonites in Germany, including those who in 1876 settled in the Whitewater and Elbing region east of Newton and in Beatrice, Neb.

[5] The Nogat River forms the eastern side of the Vistula River delta.

[6] Wedel is off by five years — Fontane died in 1898.

[7] https://www.fontanearchiv.de/bestaende-sammlungen/digitale-sammlungen-kataloge/fontane-bibliographie/fbg/liste/33-111-rezensionen

[8] Wedel’s transition to Halstead from Bloomfield, N.J., where he had been teaching, was abrupt and the timing and reasons unclear. Dorothea Franzen, in “A Short Biography of Professor C.H. Wedel” (student paper collection, 1936, Mennonite Library and Archives [MLA], Bethel College, North Newton, Kan.), claimed it happened in 1899 (7). Peter J. Wedel, in The Story of Bethel College (North Newton: Bethel College, 1954), cited 1890 (40), which is also supported by C.H. Wedel in “Tagebuch,” translated by Hilda Voth, MLA (40).

[9] C.H. Wedel, “Eine Karrikatur der Mennoniten-Indianer Mission,” Monatsblätter aus Bethel College 8, no. 6 (June 1903), 64.

[10] Franzen, “A Short Biography,” 1-4. Edmund G. Kaufman, ed., General Conference Mennonite Pioneers (North Newton: Bethel College, 1973), 155-6. Samuel S. Haury, “Die neunzehnte Februar, 1882, auf der Mennonitisches-Missions-Station, in Darlington, Indian Territory,” Nachrichten aus der Heidenwelt [special edition, no date], 7-9.

[11] Franzen, “A Short Biography,” 4-7. Kaufman, ed., General Conference Mennonite Pioneers, 157-59. Henry P. Krehbiel, The History of the General Conference of the Mennonites of North America, vol. 1 (St. Louis: printed by author, 1898), 34-35. Cornelius H. Wedel – Henry R. Voth correspondence 1889-1890, translated by Hilda Voth, C. H. Wedel Collection, MLA. James Juhnke, A People of Mission: A History of General Conference Mennonite Overseas Missions, (Newton, Kan.: Faith and Life Press, 1979), 247. James Juhnke, Dialogue with a Heritage: Cornelius H. Wedel and the Beginnings of Bethel College (North Newton: Bethel College, 1987), 56-58. Cornelius Krahn, “Indian Industrial School (Halstead, Kansas, USA),” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online (GAMEO), 1958, https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Indian_Industrial_School_(Halstead,_Kansas,_USA)&oldid=92091

[12] Franzen, “A Short Biography,” 7-8, Kaufman, General Conference Mennonite Pioneers, 159-62, P. Wedel, History of Bethel College, 70-73. See Juhnke, Dialogue, 48-60, Wedel-Voth correspondence.

[13] C. H. Wedel, “Tagebuch.”

[14] Richard A. Schmidt, “Bibliography of C. H. Wedel,” student paper collection, 1945, MLA.

[15] C.H. Wedel, “Das Grundidee des Quitt,” Monatsblätter aus Bethel College 8, no. 8 (August 1903), 87.

[16] A.J.F. Zieglschmid, “Truth and Fiction and Mennonites in the Second Part of Fontane’s Novel Quitt, Indian Territory,” Mennonite Quarterly Review 16, no. 4 (Oct. 1942), 223-46. James N. Bade, “Eine gemalte Landschaft”? Die amerikanischen Landschaften in Theodor Fontanes Roman Quitt, in Theodor Fontane: Dichter und Romancier. Seine Rezeption im 20. und 21. Jahrhundert, edited Hanna Delf von Wolzogen and Richard Faber, (Würzburg: Königshausen und Neumann, 2015), 107-39. Numerous additional examples cited in Mark Jantzen, “Reflections on America and Mennonites as Symbols and Setting in Quitt,” 91-116.

[17] Kaufman, General Conference Mennonite Pioneers, 148-153, Krehbiel, History of the General Conference, 20-78. Cornelius Krahn, “Goerz, David (1849-1914),” GAMEO 1956, https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Goerz,_David_(1849-1914)&oldid=130898

[18] “Zur Heimath,” Mennonitische Blätter. 22, no. 10 (Okt. 1875), 76-77.

[19] Roland Berbig, Theodor Fontane Chronik, 5 vols. (New York: de Gruyter, 2010), 2,737. Christina Brieger noted that Goerz was editor of the Christlicher Bundesbote, but listed it as published in St. Louis. As a result of the Summerfield connection, all of Goerz’s newspapers were printed in St. Louis until 1898, but the place of publication should be listed by the editorial office address as either Summerfield until mid-1875 or Halstead until 1893. Christina Brieger, “Anhang,” in Quitt by Theodor Fontane (Berlin: Aufbau Verlag, 1999), 305, 311. P. Wedel, History of Bethel College, 137. For listings of specific Fontane sources with citations, see Zieglschmid, “Truth and Fiction,” Bade, “Eine gemalte Landschaft” and Jantzen, “Reflections on America and Mennonites as Symbols and Setting in Quitt.” These sources, however, do not consistently note that all the material in German Mennonite sources were reprints of American, or more specifically, Kansas material.

[20] P. Wedel, History of Bethel College, 137-39. David Goerz collection, General Correspondence, 1869-1886. MLA. “Stimme aus unserm Leserkreise,” Monatsblätter aus Bethel College 8, no. 5 (May 1903), 48. Jantzen, “Reflections on America and Mennonites as Symbols and Setting in Quitt.”

[21] Mark Jantzen, Mennonite German Soldiers: Nation, Religion, and Family in the Prussian East, 1772-1880 (Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, 2010), 228. Ernst Correll, “Fontane, Theodor, 1819-1898,” Mennonitisches Lexikon, vol. 1, edited by Christian Hege and Christian Neff (Weierhof (Pfalz): printed by the editors, 1913), 661.

[22] C.H. Wedel, “Die preußischen Mennoniten in Roman,” Monatsblätter aus Bethel College. 8, no. 5 (May 1903), 52-3. Krehbiel, History of the General Conference, 40. Wedel, “Tagebuch,” 66. Fontane, Quitt, 201.

[23] Wedel, “preußischen Mennoniten,” 52. Wedel, “Tagebuch,” 26. Krehbiel, History of the General Conference, 36. Mark Jantzen, “Wealth and Power in the Vistula River Mennonite Community, 1772-1914,” Journal of Mennonite Studies 27 (2009), 93-107.

[24] Wedel, “preußischen Mennoniten,” 53. Fontane, Quitt, 202.

[25] Wedel edited together excerpts from Fontane, Quitt, 193, 197-98, 200-01, 205, “Karrikatur,” 64-5, here 65. Haury’s quote from Juhnke, People of Mission, 9.

[26] Wedel, “Grundidee,” 87.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid., 88.

[29] James N. Bade has made this argument the most forcefully — “Fontane as a Pacifist? The Antiwar Message in Quitt (1890) and Fontane’s Changing Attitude to Militarism,” in Fontane in the Twenty-First Century, edited by John B. Lyon and Brian Tucker (Rochester: Camden House, 2019), 84-102. He has also published a novel that makes Obadiah’s sermon in chapter 24 of Quitt an essential message for today, The Secret of the Glass Mountains (Pensacola: World Castle Publishing, 2019). For additional commentary, see Jantzen, “Reflections on America and Mennonites as Symbols and Setting in Quitt.”

[30] Wedel, “Grundidee,” 88.

[31] Wedel, “Karrikatur,” 63-64.

[32] Juhnke, “The Daniel Explosion: Bethel’s First Bible Crisis,” Mennonite Life 44, no. 3 (September 1989), 20-25, here 20-21. P. Wedel, History of Bethel College, 138.