Kauffman Museum at 125

[Editor’s note: The following comes from presentations prepared and/or given by Rachel Pannabecker and Reinhild Janzen at Kauffman Museum during the spring semester of 2022.]

Collecting for college and community (Rachel Pannabecker)

In 2022, Kauffman Museum , the oldest Mennonite-affiliated, continuously operating museum in the Americas and likely the world, marks 125 years. To celebrate the milestone, in February the museum opened a special exhibition titled “The Magic of Things: 5 Continents, 25 Centuries, 125 Years of Collecting.” It will remain at the museum, on the campus of Bethel College, through Oct. 9, 2022.

“The Magic of Things” on its opening day, Feb. 19, 2022

The museum’s story of collecting begins with the December 1896 issue of the School and College Journal, in which a short article announced that students and friends of the college were establishing a Museum of Natural History and American Relics. The anonymous authors requested that “Persons who are in possession of any kind of curious relics, or botanical, zoological or geological specimens, and would like to perform an act of charity for scientific purposes, here have an opportunity to do so. All donations will be thankfully received.”

The museum organizers had already collected an herbarium of plants, a cabinet of insects and small animals, and examples of metals and minerals. They noted that an owl caught on campus was being prepared for display by P.A. Penner, an amateur taxidermist. Finally, they acknowledged that “the principal part of the museum will for the present consist of a collection of Indian relics presented by missionary H.R. Voth of Arizona.”

Only one photograph is known to exist from the first 45 years of a museum at Bethel College. Published in the 1911 yearbook, Echoes, the photo shows display cases that could be holding the “metal and mineral” specimens or perhaps the “Indian relics.” The cattle longhorns mounted on the right wall suggest that someone was collecting items related to the Chisholm Trail, which passed across what is now the campus in the “olden days.” The human and cat skeletons also appear in that yearbook in a photo labeled “physiology class” – evidence that the museum collections were used for teaching.

Peter J. Wedel in the Bethel College museum in the Administration Building basement (northeast room), ca. 1910 (Mennonite Library & Archives)

In 1908, Professor P.J. Wedel wrote an article for the Bethel College Monthly entitled “A Museum a Necessity,” in which he made the point that museums, like libraries and laboratories, are essential to a liberal arts education. The Bethel museum took on a new life in 1941 after Charles Kauffman of Marion, S. D., brought his personal museum to North Newton, integrated it with the college collections, and opened the new venture to the public as Kauffman Museum at Bethel College.

Kauffman’s collections paralleled and also expanded those already at Bethel. There were prairie animals plus “exotic” animals, in an era when there were few zoos. In one display, a polar bear and a zebra joined North American deer in front of a landscape painted by Kauffman. Native Americans of the Great Plains, depicted with mannequins that Kauffman carved, joined artifacts from cultures around the world that had been collected by Christian missionaries. The material culture of frontier settlers could be seen in a log cabin, old tools and more Kauffman-created mannequins.

Photos of Kauffman interacting with college students in the late 1950s show that the collections continued to be used for educational purposes. However, Kauffman expressed disappointment that few Bethel students visited the museum on their own, even though students had free admission.

Charles Kauffman, left, with Bethel College students, 1959 (Mennonite Library & Archives)

Kauffman held a generous and open attitude toward collecting in this A-to-Z museum – everything from an arithmetic book to a taxidermy zebra. The collections grew rapidly, in part because Kauffman Museum was the only museum in Harvey County until 1966, when the Harvey County Historical Society began collecting artifacts.

Thus for 25 years, objects unrelated to Bethel College or Mennonites found their way into the collections, such as a shadowbox with a hair wreath, donated by Mrs. A.F. Hazlett, or the gun collection from Charles Smith of Halstead.

Hair wreath donated to Kauffman Museum by Mrs. A.F. Hazlett, Newton, Kan.

After Kauffman’s death in 1961, four distinct collecting directions emerged, influenced by four very different personalities.

First was John F. Schmidt, who served as museum director/curator (1964-75) in addition to his primary responsibilities as archivist for the Mennonite Historical Library (now the Mennonite Library and Archives at Bethel College). Schmidt sought to center the museum collecting around Mennonite folk history.

Second was anthropology professor John M. Janzen, who initiated collecting artifacts from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, specifically areas served by Mennonite missionaries and Mennonite Central Committee PAX workers. Janzen guided PAX worker Henry Goertz, who collected ceremonial masks from the Pende people, a project funded by the Bethel College Class of 1969.

Arlo Kasper views artifacts from the Congo in the Kauffman Museum exhibit “The Magic of Things”

Third was Cornelius Krahn, longtime director of the Mennonite Historical Library. The centennial of the 1874 migration of Mennonites to Kansas led Krahn to dream of preserving historic buildings to recreate an immigrant/settler village. In 1974, a group of volunteers moved the Voth-Unruh-Fast House from rural Goessel to the college campus. While plans for moving in an adobe house, a church and a blacksmith shop were never realized, in 1986 the Ratzlaff Barn and a little “Hoffnungsau” building were added to create what is now the museum farmstead.

The Voth-Unruh-Fast House shortly after it was moved to the Kauffman Museum grounds, 1974

Fourth was biology professor Dwight Platt. Beginning in 1984, Platt led a team of volunteers in establishing a living collection – a tallgrass prairie reconstruction with 15 species of grass and more than 100 species of wildflowers.

Dwight Platt planting the tallgrass prairie reconstruction in 1985 (Bryan Reber)

The prairie was one of the main themes of the “storyline” that took Kauffman Museum away from simply collecting and preserving to interpreting key stories represented in the museum collections.

The decision to feature select artifacts and specimens in the new permanent exhibit was a leap of faith for many in the museum’s constituency. They were concerned about what would happen to the 90% of the collections that weren’t included in the “Of Land and People” exhibition.

Museum staff committed themselves to drawing on the collections by creating a series of temporary exhibitions; organizing mini-exhibits on campus; loaning artifacts to other museums; and developing kits with real objects for hands-on teaching that school teachers could borrow.

Collecting at Kauffman Museum in the last 35 years has been guided by two trends that value interpretation. The first can be called “signature collections.”

The term is fairly recent, arising from communications and marketing language where “signature” is defined as “a distinctive pattern, product or characteristic by which something can be identified.” Kauffman Museum benefits from two signature collections that are central to the museum’s mission and that have generated significant historical interpretation.

The Martyrs Mirror collection is a joint Kauffman Museum-Goshen College project initiated by the late Robert Kreider and the late John Oyer. The copper etching plates from the 1685 edition of the Martyrs Mirror were featured in the exhibition “Mirror of the Martyrs” that premiered at Kauffman Museum in 1990, and that toured across the United States and Canada before being installed in the new building addition in 2006.

Entry to “Mirror of the Martyrs,” a permanent exhibit at Kauffman Museum (Chuck Regier)

The Mennonite Immigrant Furniture collection is based on the groundbreaking research of John and Reinhild Janzen. The 1991 special exhibition with that title largely featured borrowed artifacts. Since then, the museum’s investment in interpreting the Vistula Delta tradition has prompted donations of dowry chests, wardrobes and clocks, all priceless family heirlooms. The growth of this collection ultimately led to an expanded permanent display also called “Mennonite Immigrant Furniture” in the new addition in 2006.

Entry to Mennonite Immigrant Furniture (Chuck Regier)

Both the Martyrs Mirror and the Mennonite Immigrant Furniture collections are distinctive, derived from the museum’s mission, and have been deeply researched and interpreted by scholars.

The second trend in collecting is linked to Kauffman Museum’s special friends. From the “Of Land and People” exhibit onward, Kauffman Museum earned a reputation for developing and designing award-winning exhibitions. This led friends of the museum to pursue organizing special exhibitions featuring their private collections.

Two of these exhibit collaborations resulted in the donations of the respective collections to Kauffman Museum. In both cases, the artifacts in the collections did not have deep links to the museum’s mission. But both had compelling interpretive stories, as well as potential to generate revenue as traveling exhibits which have become a critical piece of museum financial planning.

The “Reeds & Wool” exhibition was organized by collector John Sommer and featured the Sommer-Krieger collection of textiles from the Kyrgyz and Uzbek people of Central Asia. The exhibition premiered at Kauffman Museum in 1998 and has traveled to museums in Kansas, Kentucky and Canada. Kauffman Museum last exhibited “Reeds & Wool” in 2004, and has scheduled it to return later this fall.

The “Better Choose Me” exhibition was organized by collector Ethel Ewert Abrahams and featured her collection of tobacco fabric novelties. The exhibition premiered at Kauffman Museum in 1999 and has traveled to museums in Kansas and Virginia. Kauffman Museum again exhibited “Better Choose Me” in 2018-19, with selected portions also appearing last fall to complement the “Vapes: Marketing an Addiction” exhibit.

Seeing the ‘magic’: Knowing ourselves through the things we live among (Reinhild Kauenhoven Janzen)

“There are things we live among ‘and to see them is to know ourselves.’”

George Oppen

How best, then, to celebrate 125 years of this museum and its collecting?

Since the heart and soul of a museum are its collections, Rachel Pannabecker, director emerita, had the idea to mark the anniversary with an exhibition that would feature the collections’ depth and breadth – historically, globally and thematically. This would be done by selecting artifacts that had, for the most part, never been exhibited before, that had slumbered safe and sound in Kauffman Museum’s storage wing, but that had fascinating stories to tell.

Janet Voth visits the section called The Power of Ritual at the opening day of “The Magic of Things” (David Kreider)

Who should undertake the challenge to select artifacts from the thousands in storage? Pannabecker invited all former and current museum directors and staff to act as curators, and many accepted the invitation. Each selected one or several objects that were particularly meaningful to them, and wrote down the reasons they chose what they chose. This gives the exhibition a broad scope, bringing together multiple perspectives. All the objects in the exhibition were painstakingly researched, which adds much value to the interpretive potential.

Once the co-curators had submitted their selections, Pannabecker and guest curator and former Kauffman Museum staff member Reinhild Janzen grouped the objects into six thematic clusters, which yielded the organizing principle for the design of the exhibition: The Art of Communication; The Power of Ritual; More Speed; Nature Study; Stepping Out in Style; and Making a Home.

The Stepping Out in Style section of “The Magic of Things” (David Kreider)

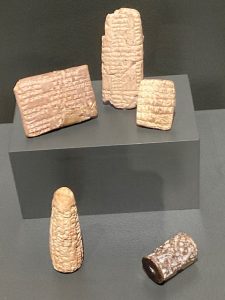

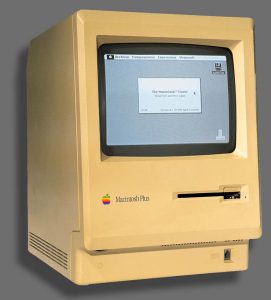

The artifacts included in these thematic groupings exemplify the astonishing global and historic breadth of Kauffman Museum’s collections. For example, The Art of Communication includes a Mesopotamian cuneiform clay tablet that scholars at the University of Chicago were able to date to 2010 BC/CE, and to translate its text, an account concerning flour. This stands in contrast to Bob Regier’s 1986 Macintosh Plus IMB Apple computer, made an ocean and a continent away from ancient Iraq, nearly 4,000 years later, in the United States of America where accounts of flour can also be found. And Stepping Out in Style features diverse clothing from five continents, among them 1890s kerchiefs from the Mennonite Molotschna colony in Ukraine and a gloriously voluminous mid-20th-century Nigerian man’s outfit.

Kauffman Museum’s oldest artifacts, a set of cuneiform tablets (David Kreider)

Bob Regier’s 1986 MacPlus (Chuck Regier)

Next challenge: an exhibition title that would be catchy and intriguing while expressing the overarching theme, the raison d’être for collecting. Janzen’s German heart would have liked to use Anziehungskraft der Dinge – in English, literally “the attraction power of things.” Of several definitions of “magic” in the American Heritage Dictionary, this one seemed to best fit the exhibit: “any mysterious or overpowering quality that lends singular distinction and enchantment, such as the expression ‘… those … breathed the magic of the past.’”

The guest co-curators of “The Magic of Things,” in alphabetical order, are Andi Schmidt Andres, who began as assistant to the director in 1993 and served in various roles before becoming director in 2020; Steve Friesen, Littleton, Colo., museum consultant with Friesen-Dakin Consulting, museum director 1976-77 (oversaw packing up Charles Kauffman’s collections in the old museum to make room for a new student center); John M. Janzen, professor emeritus of anthropology, University of Kansas, museum director 1983-92; Reinhild Janzen, professor emerita of art history, Washburn University, curator of cultural history, 1983-93; Dave Kreider, staff 1985-88 and 2000-present, currently exhibit technician; Rachel Pannabecker, who began as collections assistant in 1984, museum director 1996-2014, currently special projects volunteer; Dwight Platt, professor emeritus of biology, Bethel College, natural history consultant since 1985 and ongoing senior prairie consultant; Austin Prouty, exhibition assistant 2020-22; Bob Regier, professor emeritus of art, Bethel College, exhibit designer since 1985 and ongoing senior design consultant; Chuck Regier, who came on staff in 1985, currently curator of exhibits; Michael Reinschmidt, Oklahoma City, museum director 2018-20; Kristin Schmidt, museum assistant 1999-2022; and Renae Stucky, access services librarian, Bethel College, collections manager 2016-18.

When P.J. Wedel wrote in 1908 that “The Museum [is] a Necessity,” he was giving one of the most succinct definitions of what a museum is. The objects people make become concretized evidence of what it means to be human, many outlasting the lives of those who created them. Objects – whether a motorbike or a painting – can be, must be, “read” like books. They are primary sources, embodying thought and how manual skills and ingenuity transform matter into a thing that carries meaning.

Kauffman Museum’s collections, when subjected to serious research, offer remarkably rich glimpses into the lives of people and cultures around the world. “The magic of things” can give profound insight into the mysteries of life and death, the visible and invisible, the here and now and memories of the past.