Losing Lawrence Hart (Feb. 24, 1933-March 6, 2022)

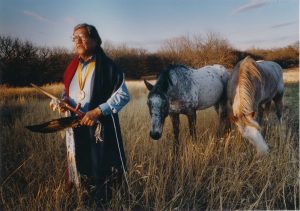

Lawrence Hart (Cyrus McCrimmon, Rocky Mountain News, by permission of Betty Hart)

It is a drive I love, but today, one I have dreaded – going south to Oklahoma for the viewing and memorial service for Lawrence Hart, mentor, friend, nationally known leader as one of four Principal Cheyenne Chiefs, and a beloved Mennonite pastor who died March 6, 2022, after a long illness. When my husband Doug and I last stopped to visit Lawrence and Betty in the summer of 2021, Betty told us as she walked us to our car that it was time to call in hospice care for Lawrence. Lawrence had been seated in his chair in the living room during our visit; he answered our questions with “yes” and smiled, but we could see that time was running out for him. He was 89 and had for many years had to curtail his public life of service to tribe and church.

Now, I wondered as I drove toward Clinton, Okla., on the route I had begun driving 20 years earlier to interview him, how a man of this stature – who had bridged his Cheyenne birth and Mennonite training – would be laid to rest. Lawrence had made clear to Betty his wishes for the service and burial, but who could properly provide a service for the man who had stood all his adult life with a foot in two worlds, Cheyenne and Mennonite? There was no one.

I remembered again his instruction to me as I began my interviews and acknowledged that as a white Mennonite woman, I feared I might ask insensitive questions or reveal his life in culturally inappropriate ways, use offensive vocabulary choices, or present his story through a lens he would not choose. He paused then, as he always did. Long silence. Finally: “I would not wish to be seen as boasting.” I knew too well that there was no one left to do for Lawrence what he had been doing at the services of those, including my own family members, disappearing into the Oklahoma soil for miles around Clinton for decades: send the deceased on their journeys with a pastor’s words of Christian hope, spoken in Cheyenne if the deceased was a part of the Cheyenne family.

The viewing for Lawrence was held in the late afternoon at the little Koinonia Church, which stands stark and alone on an incline just east of Clinton across the Washita River. The original church building had been moved across the road (Route 66) north from the Mennonite missionary parsonage on the old 20-acre mission station where Lawrence and Betty have lived and served for nearly 60 years. As I entered the back foyer of the church, I was comforted by the usual sight of the women bustling in and out of the tiny side kitchen to set food on tables. The sensory memory that came to me in that moment was of the wonderful taste of the traditional dried-corn soup I once ate here and never forgot, emblematic of the hospitality always shown to visitors here, and the way the Cheyenne women, especially, always took me in.

Inside the simple little sanctuary, a hush and darkness that was unfamiliar. Lawrence was lying at the front of the church in a beautiful wood coffin. He had requested wood, but his family had no time to get one hand-built in the four-day period prescribed before burial, so they purchased this one. This is how it works when we wish to honor our dead. The realities impinge upon our best hopes. Lawrence would have loved an Amish-built box.

In truth, Lawrence had lived all his life with the contradictions of real life in the 21st century over against what might be sustainable of the lifestyle his grandparents had taught him in the first six years of his life, when he was completely in their care, learning Cheyenne ways from a generation older than he would have known had he lived with his parents across the yard. Instead, he spoke only Cheyenne with his grandparents, the matriarch and tribe’s midwife Cornstalk and Chief John Peak Heart (later John P. Hart), the latter born in 1871 to Afraid of Beavers and Walking Woman, losing the original “Peak Heart” at Carlisle Boarding School. Lawrence began his life as a Cheyenne boy learning Cheyenne ways, becoming from birth the bridge to Cheyenne thinking and peacemaking that was his destiny for nearly 90 years.

The wood coffin is surrounded by Lawrence’s medals, moccasins, bonnet and other Cheyenne symbols of his life. I note the serenity of his face in the open coffin. It is the same serenity one could count on in his life; Lawrence was always composed, always calm, always welcoming. But now he will not smile. And he will not sing out in his deep and loud leader’s voice the Cheyenne hymns I have so often watched him lead from his spot on the south side of the sanctuary where he sat before going to the front to preach or teach or discuss.

Suddenly, I am very sad. I slide into the back pew. My cousin from Elk City soon slides in beside me. Her parents were good friends of the Harts from the years they attended First Mennonite in Clinton. Lawrence’s family surrounds him at the front. People file slowly forward to speak to them. A few will stand and speak alongside the coffin – a young man for whom Lawrence was a life model, counsel and guide; an older woman who reminds everyone there of Lawrence’s faithfulness, that he always came, drove for miles to be there when a family member died. She had lost a close loved one and was surprised that Lawrence and Betty drove the distance with his advanced age and declining health. “Oh, Lawrence, you have come,” she said when he arrived. “Of course, I had to be here,” he told her. Lawrence knew the peace he could bring to a Cheyenne burial by his presence, his words in Cheyenne.

In fact, Lawrence taught me the value of presence, of “sitting with.” Extrovert that I am, words always poured from my mouth when we were together. Sometimes when I was finally quiet after rephrasing my question three times to get an answer I wanted from Lawrence, he sat quietly for some time, maybe to allow me to hear my words echoing in his silence. And I often rethought what I had just said. And rethought it again. And sometimes the question rightfully disappeared into the silence.

Sometimes Lawrence mentioned that he needed to go “sit with” someone who disagreed with what he was doing. Once, he suggested that he might ask me to go “sit with” someone in the Topeka community, where I lived then, who disagreed with him. I was terrified. What would that mean? It turned out he did not call on me to do so. I doubted I would have known how to do it. Just to sit with someone in silence? Or did it mean that he sat until the other spoke, allowing space?

We sit together at the viewing and finally, after it is clear that friends and family have spoken, I go forward, lay my hand on his coffin and try to say what Lawrence’s life has meant to me and many Mennonites across the country, even beyond national borders. But my words are inadequate as I hear them fall into the silence of the little Indian church.

Words are always inadequate in the face of death. I wonder if I should have remained silent. I wonder whether I should have laid my hand on a chief’s casket as I did without thinking, wanting to reach him somehow. I remember the day I was talking with Lawrence about the missionaries, the boarding schools, the way Cheyenne culture was abused and ignored by the Mennonite missionaries. I felt a need to apologize for the Mennonites. “It would have been better had they never come,” I mumbled quietly, though I knew that Swiss missionary Rodolphe Petter’s compilation of the Cheyenne dictionary made him a hero in Lawrence’s eyes. He didn’t criticize the missionaries, though he sometimes told stories that made clear their mistakes. There was long silence after my awkward apology suggesting that the missions were a failure. Lawrence looked at me directly then – he often did not, for sure when we were eating together. He addressed me directly, a moment I won’t forget. “No,” he said quietly. “We needed the Good News.” Once more, he had provided a bridge on which to move forward.

Betty had called me to ask that I read Lawrence’s obituary at the funeral service the next day. I was highly honored. Their oldest daughter Connie had composed the obituary and copied it to me the night before. However, when I saw my name listed among those “officiating” in the program for the service, I wished that I had added much more to the obituary. There was so much to tell about Lawrence and his life’s transitions, even much that did not get into the book I wrote about him (Searching for Sacred Ground, Cascadia, 2007). Connie had given me permission to add personal stories, but it was the same dance I always did in presenting Lawrence’s story publicly: what if I said something culturally inappropriate or weighted too heavily certain Mennonite aspects of his life? How would I know the norms of a Cheyenne memorial service, even for a Mennonite pastor? It was always better to be in the room when Lawrence spoke for himself with his uncanny ability to say the right words when called upon in any event or situation, whether he had prepared or not.

The memorial service program features the photo of Lawrence in the field with the horses, the same one we used on the book cover. It has been enlarged by the funeral director to set prominently in the front of the community center. In the photo, Lawrence wears a denim shirt draped with his red-and-black chief’s blanket and medal. He holds a beaded bag, eagle feathers and pipe, and looks into the sun.

The Isaiah Scripture he loved is printed on the inside cover of the program: “But those who hope in the Lord will renew their strength. They will soar on wings like eagles, they will run and not grow weary, they will walk and not be faint” (40:31). These words are right for Sky Chief, who soared in the sky in his earlier military pilot’s life before he became a chief. He followed in the tradition of the long line of chiefs who were first great warriors before they disavowed warrior ways. He who walked and did not grow faint all his life until illness beset him. That one who soared in the skies is the hero the Cheyenne people have come to celebrate today. Sky Chief, who as a youth determined to keep his body strong and resist the temptations of the world so that he might be accepted by the Marines to become an important fighter pilot and instructor. I recall again the story he told me of lying in the cotton field, where he was picking cotton as all kids had to do growing up around Hammon or Clinton in the 1 930s and ’40s; my parents too told stories of picking cotton. There Lawrence watched planes fly high above him in the sky and determined that he would someday fly. He would rise above this hard cotton-picking work and soar with the eagles!

The chiefs and singers sit together in a prominent place in his service, wrapped in the same blankets pictured on Lawrence, but most of them appear to me to be too young for Lawrence Hart wisdom. I remember his most famous story, of the reenactment of the Washita battle when he was a young chief: how the arrival of Custer’s Seventh Cavalry turned a reenactment into something too real, and how he learned from the old chiefs to quell the turmoil with an act of restorative justice, giving a blanket to the young reenactors who in turn promised never again to play the battle song “Garry Owen,” so often used against the Cheyenne people and which they had heard again that day. Always, it seemed, Lawrence knew how to lay over the blanket, wrapping in love the imperfect human form. The Lawrence Hart wisdom of an old chief will be buried today.

I am nervous to read the obituary. I have worn my best black suit, but I see that I needed a black shawl with fringes. Yet I believe that Lawrence would have approved of my attempt at a dignified, academic look. He was proud of his academic achievements. I stand before his flag-draped casket in the large community building of the Cheyenne and Arapaho people, a prominent picture of Lawrence as Sky Chief alongside his fighter jet on my right, his large feather bonnet prominent above the picture, and on my left, a large but simple black and white picture taken inside the white tent with other chiefs the day he became a chief in 1958, the same year his grandfather and his mother died.

In the first line of the obituary, I must pronounce the words for “Sky Chief” in Cheyenne, He’amavehonevestse, and despite being schooled by Lawrence’s son-in-law Gordon Yellowman, also a Cheyenne chief who has taken over performing many of Lawrence’s responsibilities, I garble the pronunciation. I warm up to my task as I am allowed to read of his many services to the world. And then I can return to my place on the stage to sit out of view behind his bonnet and listen in silence while the singers sing from their seats, their strong deep voices singing in the Cheyenne language.

The songs sound like Cheyenne hymns of mourning – church songs, of course, no drum. Heartfelt. Soulful. Moving, even if you do not understand the words. The singing feels familiar to me, and I love sitting out of view, listening to the rising and falling cadences of the Cheyenne language that seem to emerge unexpectedly from deep within the singers. I love the way the song circles round and repeats, growing more and more familiar until I almost feel like I could join in. Again, I want to weep; I believe I hear Lawrence’s voice in the voices of the chiefs. And in that moment, I remember the story I used to close Searching for Sacred Ground. A woman elder and descendant of Chief Black Kettle stood one evening listening to Lawrence sing after a program he had given. Later, she came forward to report to him that as she stood in the doorway while he sang, she heard clearly the ancestors singing with him outside in the night.

With whom will the ancestors sing now?

The Mennonite spokespersons – Heidi Regier Kreider, Western District Conference (WDC) conference minister, Kathy Neufeld Dunn, WDC associate conference minister and liaison to Koinonia Mennonite Church, Iris deLeon-Hartshorn, associate executive director of Mennonite Church USA, and E. Susan Hart, recently appointed pastor of Koinonia – are all women. Lawrence had great faith in the leadership of women and never failed to remind me that Cheyenne life was matriarchal, that the Mennonite church would benefit from more women in leadership, even perhaps suggesting that women were the future of the church. They certainly are the backbone of Koinonia and perhaps always have been. Lawrence trusted matriarchal intuition, the way women are in their very bodies, tied to the earth’s time and tides. He often remembered how the night before the Washita massacre, Chief Black Kettle’s wife, Medicine Woman Later, had argued unsuccessfully long and hard for moving the camp that night even though it was late and the weather was bad. She feared exactly what then happened at dawn.

Like my own father, Lawrence never seemed to wish I was a man with inherited male authority as I told his story. He trusted my words and was mostly unwilling to correct me. That aspect of our work together always gave me pause. It was as if for him relationship was more important than facts or analysis. Lawrence relied heavily on oral culture, the stories he had learned as a boy, the wisdom of the elders never written down. Such storytelling is artful and fluid, much more attuned to audience and purpose than historical fact. Though Lawrence knew his history well, the stories became like parables, powerful lessons and lifeways. Sometimes I know he felt I was missing the point when I pressed for more precise dates, more specific details or accuracy.

When I think of Lawrence as artist, I remember again the winter he built with his own hands a beautiful wooden display unit for “The Cheyenne Way of Justice,” an exhibit he designed for the 2004 Sovereignty Symposium of Oklahoma tribes in Oklahoma City. His exhibit had lifted some of the stories about traditional Cheyenne practices of justice out of the classic text, The Cheyenne Way by Llewellyn and Hoebel (1941), still studied by jurisprudence experts for its Cheyenne examples of restorative justice. Lawrence had flown in to Oklahoma City and the Sovereignty Symposium his friend Howard Zehr, internationally known Mennonite scholar on restorative justice, to authenticate to the gathered tribes that the Cheyenne ways of justice were, indeed, true models of restorative justice as defined by Zehr. It was one of Lawrence’s proudest moments to present his people’s practices long before “restorative justice” as a label was widely used. For me, it was the perfect example of Lawrence’s unique ability to bring together his sometimes bifurcated lives as Cheyenne leader and Mennonite pastor.

When the memorial service is finished, attenders file past the table at the back of the auditorium on which I notice a stack of white tea towels. Some people take one as they leave. The Cheyenne chiefs are honorary casket bearers and we all follow into the icy Oklahoma wind to find our cars and drive across the road to the Red Wheat Allotment where Lawrence has chosen to be buried, on the site where the mission church once stood, not far from Lawrence and Betty’s house.

A large white chief’s tepee has been erected alongside the hand-dug burial spot up the hill. It is notable, and I am powerfully moved, that Lawrence has chosen to be buried on this site, for him sacred ground, where the old mission church once stood. I understand at once his choice of Red Wheat’s allotment, a powerful symbol for him of who he was, Cheyenne and Mennonite, the coming together of two peoples, in an act of God which symbolized his destiny (he had spoken about this destiny in his commencement address at Bethel College in 1998). The name of the Cheyenne woman who took this allotment is translated as Red Wheat, and she deeded 20 acres of her allotment to the General Conference Mennonite Church Board of Missions, which built the church here in 1898.

I regret again that Lawrence became ill before we could take up a project he had longed to research in the old records he still held: how many of the old chiefs had assented to the question Petter had first proposed to Chief Red Moon near Hammon in the first Mennonite encounter with the Cheyennes: “Will you hear the Good News I have translated into Cheyenne with Whiteshield’s help?” Petter reported that Chief Red Moon had answered, “Very well, we shall like to hear what we have never heard before,” and he called his people together to hear what Petter offered. Lawrence stood squarely in this leadership tradition and believed that most of the Cheyenne chiefs had been favorably disposed toward Christianity as he reviewed the names on the rolls left to him by the missionaries.

At the burial site, I stand up the hill out of the wind behind a large black pickup with some who helped prepare the site. We watch as the chiefs follow the casket across the windy pasture and up the hill, singing, to the hand-dug opening in the earth where Lawrence’s flag-draped coffin will be placed. Chief Gordon Yellowman wears Lawrence’s feather bonnet. Daniel Mosburg, pastor of First Mennonite Church in Clinton, a friend of Lawrence who recently served him his last Communion, Betty tells me, reads the 23rd Psalm. Uniformed Navy military representatives stand before the coffin as the gun salute sounds over the wind and “Taps” is played. The Navy men struggle mightily with white gloved hands in the wind to fold the flapping flag into the tri-cornered memento they will hand to Betty in the tent the funeral home has erected for the family alongside the gravesite.

The chiefs sing on in the tearing wind, and I hear voices in the crowd sing with them the Cheyenne songs familiar to many of those gathered here. It occurs to me after the flag is removed that the box is too beautiful to be placed into the ground. A woodworker himself, Lawrence would have thought so, I am sure. Then I note that placed upon the beautifully finished wood of his coffin is one of the rough, hand-built Return to the Earth boxes Lawrence commissioned with the help of Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) for burying Native remains left on shelves around the country, one of Lawrence’s signature projects initiated by MCC and taken up by other denominations and organizations. He told me once he hoped he could live to see all the tens of thousands of remains buried – returned to the earth – before he died. Now, this hand-built box of unfinished wood designed by Amish craftsmen to bury the remains of his ancestors has been lovingly packed by his wife and granddaughter with his own personal items for the journey to accompany him in the Cheyenne way. It is right. I am grateful.

One of the chiefs comes to place into the open grave, now ready to be filled from the large pile of red earth before it, four sprigs of sweetgrass or sage, some fragrant pieces of earth’s growth placed into the four corners. Lawrence always emphasized that the cardinal directions for the Cheyenne people were not north, south, east and west, but in the corners – northwest, southwest, northeast and southeast. How many times I have watched him pray, facing each of the four cardinal directions. Always before, I saw this movement as an address to the earth and skies, usually of gratitude for existence, for the earth. Normally, as I watched him go from corner to corner to address the Great Earth Spirit, I thought of the four seasons, or the four elements of fire, air, water and earth. Today I remember the four stages of our lives: birth, youth, adult or elder, and death.

They have lowered the casket into the ground, and the people have walked by to take a handful of red earth and place it over his coffin to cover him. “Thank you, Lawrence, for your amazing life shared with me and with us,” I breathe as I drop the wet earth over him.“Walk on in your journey wrapped in God’s peace.” And then, suddenly, I sense excitement in the crowd as they look to the sky in the west. A plane is coming, and the white tea towels begin waving. All around the pasture former military men stand at attention. Gordon Yellowman, now one of the four principal chiefs of the Cheyennes, raises Lawrence’s feather bonnet high into the sky in a salute as the plane comes low over the burial site and the tea towels clap and flip and pop in the wind like kites. Women ululate. Men yip. The plane tilts its wings side to side as it flies low over the site, thrilling the people.

And then the plane disappears into the east, a reenactment of the day Lawrence flew back to his base after becoming a peace chief in 1958, nearly 65 years ago. That day too, the people waved their tea towels in honor of him as he left the ceremony and flew his plane low over the gathered crowd as he had promised them, a day that christened him Sky Chief, a day the local Cheyenne people in this area never forgot. It is moving to see the plane disappear into the sky, and more than one of us wipes a tear as we stand on the hillside together in the cold.

We return then to the community center for the meal, generous helpings of food, especially beef and fry bread among the piles of side dishes. I am treated as an elder and served by Lawrence’s daughter-in-law Melanie, who laughs at my protests. Elders are served at the table. Everyone else stands in line. I am remembering that traditionally, chiefs always ate last to be sure the people were fed. The mark of a good chief was servant leadership and generosity, displayed today by Lawrence’s family – especially important for a chief’s family – with piles of gifts for the giveaway.

First, the chiefs who have been singing and praying throughout these ceremonies are called forward, and then all of us who had a part in the service, or even attended, are given gifts. Connie, Lawrence’s older daughter, gives me a beautiful white shawl decorated in blue with long white fringes to wrap around my shoulders. More and more people are called forward, honored aloud by Chief Gordon Yellowman speaking for the family, all lined at the front. As each of us is called forward, the family members take the hands of dear ones. Betty, especially, receives hugs and condolences. There is laughter and shared care and memories. And then, finally, the family asks that anyone who did not receive a gift come forward to receive the gifts still on the table!

Primarily practiced at a chief’s feast, a funeral or a powwow, the traditional giveaway often happened both as a way to honor and show generosity but also, especially in earlier times, as a way to distribute to those in need. Because the giveaway was seen by the U.S. government in early settlement years as anti-capitalistic, anti-civilized in the sense of not properly respecting the ownership of property, not valuing the accumulation of wealth, not encouraging Native peoples to become good American consumers, it was outlawed as a practice of Native American religion for 50 years. However, Native people who practiced the giveaway found ways to continue the tradition, and giveaways continue to be an important practice at funerals and powwows, naming ceremonies and graduations, especially to publicly announce a change in life stage or a new role. Unlike with the typical American shower or potluck, the Native honoree gives to others, to suggest gratitude for their own blessings. It is a good way to end this day of honoring Lawrence’s life, a life of giving, teaching, preaching and service, of prophetic leadership and care for his people, whether Cheyenne, Mennonite, Cheyenne Mennonite, or simply in need.

From the beginning of their return to the Clinton community to serve, Lawrence and Betty looked for need and tried to meet it. During the viewing and family visitation the day before Lawrence’s service, Betty and her children recalled the 22 foster children they had taken in during their early years in the community, out of love and because there was a need. They smiled to remember that many in the community believed incorrectly for years that their youngest child Chris was a foster child they had adopted, so integrated were these foster children into their own family. We are, indeed, a large family of loved ones Lawrence leaves behind today to grieve his loss.

Lawrence told me once that he usually liked to use two Cheyenne phrases at services he performed for the death of a Cheyenne elder: Zi o vo ssi dan ni, I di sshi pi vi ah mo kho vi ssta vi, “This person has gone on his journey in a good way,” and Hi yah i i sshi vo mah zi yo o, “Perhaps they have seen each other again.” I trust that someone has spoken these Cheyenne phrases for Lawrence’s journey today in song or word. May it be so.