Thinking with our hands

Karen Reimer is a conceptual craft artist, a Kansas native who now lives in Chicago. She has degrees from Bethel College and the University of Chicago (MFA). From Feb. 9-April 24 of this year, Reimer’s work was on display at the Salina (Kan.) Art Center in “The Map vs. the Walk.” The title points toward, in the artist’s words, “knowledge vs. experience,” or to balancing abstraction and sensation. The exhibit was a partial overview of her work over about 30 years, starting with her first embroidery series from the late 1990s.

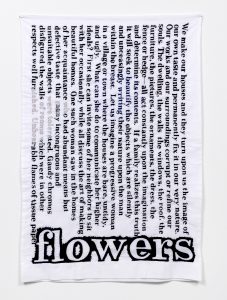

Reimer works with fabric, embroidery and quilting. She tries to slow down human processes of assessing and classifying information, and she is drawn to the ambiguous and the not easily classified. Through her hand-stitched work, she looks at language, cultural assumptions and value systems.

Reimer’s choice of craft as her genre is homage – intentionally or not – to many generations of Mennonite women (and of women in general, in North America and globally) and “women’s work.” Likely few women who spent painstaking hours creating quilts, clothing and decorative needlework thought of what they did as art. Nonetheless, that is what they created.

In her Feb. 23 artist talk for “The Map vs. the Walk” at the SAC, Reimer reflected on her own use of craft to create works that, over the course of decades, comments on feminism, cultural expectations (e.g., of women and femininity), cultural rigidity (e.g., seeing in black and white with no recognition of the gray), climate change, and seeing something new in the quotidian (what some would call trash) – among many others.

Solution to Last Week’s Puzzle (1999); 5 x 4 1/2 inches

I’m going to start by talking about why I’ve chosen to work in this medium: Why craft?

One of the reasons I do craftwork is that I was brought up doing it. I know how to do it easily and well. My family is full of crafters – my mom could quilt for the national team, as could her mother and a few of her sisters – and so I learned how to do this stuff at my mother’s knee, as they say. I know how these techniques work and I know how these materials will act.

Richard Sennet, who wrote the book The Craftsman, said about musicians that they have to have 10,000 hours of practice to know their instruments so well that they are then free to be creative, to improvise. I’ve put in my 10,000 hours with embroidery and quilting.

Cold Comfort (2001); collaboration with Constance Bacon, installation at Hyde Park Art Center, Chicago

Another reason I work in craft is for its cultural associations. Craft is a way to think and talk about those associations and the values behind them.

The kind of craft I do has traditionally been seen as “women’s work.” Historically, fiber craft has been associated with useful items in private domestic life. Private life and domesticity are considered women’s domain, and have therefore been considered dismissible.

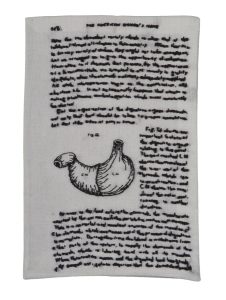

The American Woman’s Home (1999); 7 x 5 inches

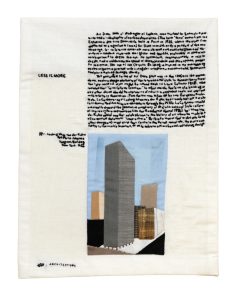

Related to that, craft has been associated in relatively recent art history with bad or at least unsophisticated taste. Craft history is the history of decoration. Modernism rejected decoration. Adolf Loos, an important Modernist architect, said ornamentation was a crime. (Arguably, this man was hysterical in the Freudian sense.) Mies Van der Rohe, another celebrated Modernist architect, famously said, “Less is more.”

Craft, with its tactility and complexity, says “More is more.”

Taste is about social class, which is about money. I think only people who have always had plenty say things like “less is more.”

Quoting Pierre Bourdieu, a French sociologist: “The tastes of freedom can only assert themselves as such in relation to the tastes of necessity, which are thereby … defined as vulgar.”

Less is More (2000); 10 x 8 1/2 inches

So for me, working in craft was a way to sort of thumb my nose at high class, ultraclean, highly finished, less-is-more “good” taste.

Now I need to say that the art world’s rejection of craft has really pretty much gone away in the years since I first started working [in this genre]. Craft is definitely not dismissed the way it used to be. There are a lot of very respected artists working in craft now and no one blinks an eye to find it in high-art museums.

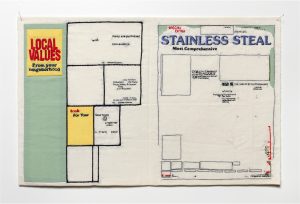

Local Values (2001); 22 x 13 1/2 inches

Another reason I like to work in craft is that it’s democratic, in the sense that it’s available to anyone. Anyone can do it. Craft is a skill, not a talent. There is no such thing as a genius embroidery stitch, the way people might talk about a genius brush stroke in a painting. The better you are at craft, the more exactly the same each stitch is. The technical work of one really good embroiderer looks pretty much the same as the work of any other really good embroiderer.

Because it is a learnable skill, anyone can do it. It’s not easy but you just have to be able to be patient and careful, not special or brilliant or heroic.

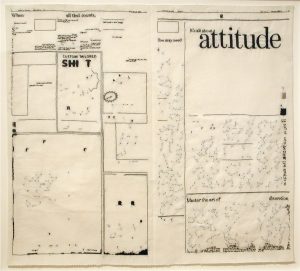

Chicago Tribune, Jan. 20, 2002 (2002); 21 3/4 x 24 1/2 inches

Yet another reason I like craft: craft is slow. It is outrageously slow. In a world where everyone is as busy as we all are, it is really unreasonable to do this kind of work. Completely inefficient. Machines can do this work now, and they can do it much faster, and arguably better – depending on how you define better – than I do.

E.P. Thompson, a British labor historian who wrote a biography of a great craftsman, William Morris, said, “The uptake of standardized, synchronized timekeeping was essential to ensuring the organization and discipline required for the rapid expansion of industrial capitalism.”

So for me, choosing to do work this slowly is a kind of resistance to Fordism and Taylorism – to the regimenting of bodies and labor to produce capital faster and faster. I want to insist that you can’t make a one-to-one exchange between labor and money. Hourly wages for labor are arbitrary.

Brown Cube (2005); 20 x 20 x 20 feet, installation at Durand Art Institute, Lake Forest, Ill.

Another reason I do craft is the pleasure of repetition. This is less political and more personal.

Taking the same stitch, making the same gesture, over and over, stops time. It makes time circular rather than linear. We generally know time is passing because we compare one moment to the next. If every moment is the same for long enough, it stops time – or rather, it stops us being aware of time. Maybe it’s like meditation, although I think people who meditate have loftier goals. I am not trying to empty my mind or lose my ego. I just enjoy the mental space repetitive labor puts me in.

I have to stop here and say that the repetitive labor I am doing is not coal mining. I don’t want to say that people doing really heavy, difficult, repetitive physical labor are in an enjoyable flow state. I’m using the term “labor” very broadly here to mean any work one does with their body.

Twelves (portrait) (2008); embroidered napkin, one of 12 pieces of embroidered household linen

That said, I know that many people experience the kind of slow repetitive work that I am doing as a kind of torture, and people frequently feel free to tell me that what I’m doing is insane. If I am, I don’t believe it’s because I enjoy slow repetitive work with my hands. I find it not exactly restful, but very satisfying somehow. There is a level of focus that you can get by paying really close attention to tiny differences in almost identical actions. Keeping my hands moving lets my mind work smoothly.

I believe we can think with our hands. I frequently say that I figure out how to make something by making it. I solve the problem with my hands as I go. We all do this, whether we think of it in those terms or not. Our hands are connected to our brains just like our eyes are.

There is some recent science in psychology and the biological sciences that supports the idea that thinking doesn’t happen in an abstract, disembodied mind. This is known as embodied cognition. Professor Susan Goldin-Meadow of the psychology department at the University of Chicago wrote in a recent issue of the journal Cognitive Science, “We change our minds by moving our hands. Our bodies, and particularly our hands, play a huge role in how we think. Physical acts are a way of working out our thoughts.”

A gallery of more recent work by Karen Reimer

Untitled (Henderson) (2011), from the series The Domestic Partnership of Heaven and Hell; embroidered pillowcase, 30 x 20 inches

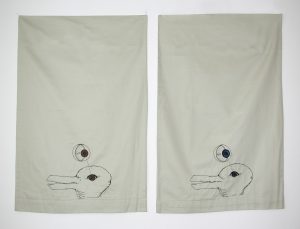

Rabbit/Duck Gets Married (2014); embroidered pillowcases, 29 x 30 inches each

Shoretime Spaceline (2016); installation at Hyde Park Art Center, room: 25 ft. x 78 ft. 8 in. x 32 ft. 4 in.

Sleeping Under the Sky/Sleeping Under the Lake #1 (2017); quilt, 90 x 96 inches

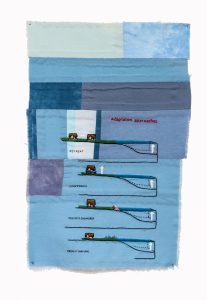

Adaptation approaches (2020); 16 1/2 x 11 inches

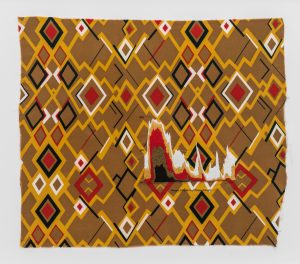

Percent Area for High Plains Drought (2020); 27 1/4 x 30 1/2 inches

[All images copyright of the artist and courtesy of Monique Meloche Gallery, photographer Tom Van Eynde]