Elder Wilhelm Ewert of Obernessau and His Defense of Nonresistant Faith

One hundred fifty years ago this year Elder Wilhelm Ewert and his family migrated from Obernessau in Prussia, today Mała Nieszawka, in Poland, to Marion County, Kan. He was a prominent leader in efforts to reject military service as the draft was being imposed in those days in both the German and Russian Empires. He visited Russia and North America along with delegates from the Russian Empire to search for suitable locations where Mennonites could live out their faith. He was a strong advocate for placing faithfulness to the Bible ahead of social considerations and in his generation made one of the strongest pleas in print for the importance of missions in maintaining a vibrant church. After settling in Kansas near the town of Hillsboro, he became the founding elder of Bruderthal Mennonite Church, where he then played an important role in new educational and mission activities among Mennonite immigrants in Kansas.[1]

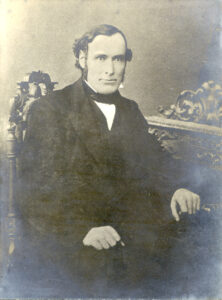

Wilhelm Ewert, ca. 1880. Photographed by Riesen at Newton, Kan., used courtesy Mennonite Library & Archives

This anniversary is a useful occasion to renew attention to Ewert’s call for a living, faithful church rooted in love of God and a heart for the lost. His main articulation of this vision for the church was published in 1873 in the German Mennonite newspaper Mennonitische Blätter and is reprinted in this edition of Mennonite Life. He was responding to a series of articles advocating for accepting military service in some form by Jakob Mannhardt, elder of the Danzig Mennonite Church and publisher of that newspaper. Mannhardt had argued that Mennonites should accept military service, preferably as medics, but the decision should be up to each individual member. He provided theological arguments for aligning Mennonite church views with embracing and defending their neighbors in the German Empire as an important way to live out Mennonite and Christian values. While some other Mennonite leaders opposed Mannhardt’s views, they were in the minority and Ewert was the only one to provide a written rebuttal to the challenge of accommodating to social pressure.[2]

In addition to his written testimony, Ewert and his congregation left another legacy in Prussia, now part of Poland. The cemetery of his congregation was in the neighboring village of Wielka Nieszawka or Großnessau. Today the Olendarski Ethnographic Museum, an open-air museum dedicated to telling the story of Dutch and Mennonite settlers in this area, is centered around this former Mennonite cemetery. The museum is planning a small exhibit this year around this important anniversary, so that Ewert will be commemorated in Poland 150 years after his departure.[3]

Wilhelm Ewert was born Feb. 23, 1829, in Stronske, just across the river from Thorn/Toruń. He was the youngest child and the only one from his father Peter’s third wife, Maria Thiart, who died just a couple of years after his birth. He received a better education than his older siblings, attending the Bürgerschule in Thorn.[4] He trained to be a carpenter and builder, but after marrying Anna Jantz on May 30, 1854, and acquiring thereby a well-established farm, he turned to agriculture. He was baptized in 1843 by Elder David Adrian and elected preacher in 1860. By that time his oldest brother Peter had become the elder. At the request of the congregations in Russian Poland in Deutsch Wymyschle/Nowe Wymyśle und Deutsch Kazun/Kazuń Nowy, the two in 1863 had planned to travel there together to assist in elder elections, but the Polish January Uprising against Russia made travel too dangerous. Peter’s death early in 1864 changed those plans even further. Wilhelm instead arranged for elders Peter Bartel from Graudenz/Grudziądz and Johann Penner from Thiensdorf/Jezioro to travel with him in June and July. Thirty-two young people were baptized in Deutsch Kazun and six in the branch congregation in Wola Wodzyńska. H. Bartel was elected elder in Deutsch Kazun and Gerhard Bartel in the Frisian portion of the congregation in Wymyschle. On July 1, 1866, Wilhelm Ewert was elected elder for the Obernessau congregation. His family life was difficult in this time – of 13 children born between 1855 and 1870, only six survived past childhood. Five died as infants; a daughter, Minna, died at age two in 1867; and in 1871 son Paul drowned in the Vistula River at age seven, while under the supervision of his 13-year-old sister Auguste, adding another level of sorrow to the family.[5]

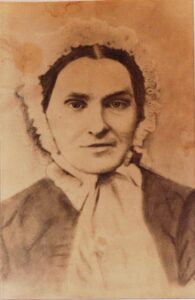

Anna Jantz Ewert

From 1864 to 1870, the Mennonite principle of nonresistance in Prussia was sorely tested by the three wars of German unification. Until this time, under the Prussian Mennonite Edict of 1789 Mennonites were granted exemption from military service in exchange for extra taxes and restrictions on their civil rights that prevented them from buying property from a non-Mennonite or marrying a non-Mennonite. A change in law in 1868 required that they serve as non-combatants; an additional law in 1874 restored their civil rights. In response to the requirement to serve in the military, in 1870 Ewert traveled extensively with Preacher Peter Dyck from Tiege/Tuja throughout the Russian Empire looking for options to settle there, including in the regions of Kherson, Tauride, Caucasus, and Kuban. Yet by then it was clear that the military service exemption in Russia was also under threat. Back home in Prussia, Ewert signed many petitions with other elders to government officials seeking to change the law or regain an exemption for those Mennonites who were not willing to serve. As part of competing petition campaigns, in congregations where the leadership opposed military service, members who supported it in 1868 and 1869 circumvented the traditional role of leaders in organizing petitions and created their own signature drives. Ewert’s small congregation of just under 100 members was the only one where no members signed either petition in favor of military service, although this may have had something to do with their relative isolation from other congregations. In November 1872 he traveled with Elder Gerhard Penner of the Heubuden congregation to Berlin to visit and encourage Johannes Dyck from Penner’s congregation, who had been imprisoned there since April for his refusal to serve in the military. Elder Penner, coming from the largest Mennonite congregation along the Vistula River, was the most prominent opponent of military service.[6]

Most Mennonites in Prussia, however, were willing to serve as regular soldiers or as non-combatants at this time. It was in this setting that Elder Jakob Mannhardt of Danzig wrote his series of articles in 1872 making the argument for Mennonites to join the army. After waiting for almost a year in vain for the main leader of opposition to military service, Elder Penner, to respond in writing, Ewert finally wrote his own response in 1873, a powerful critique of Mennonites’ accommodating to German nationalism at the expense of their traditional loyalty to the biblical way of peace.[7]

Ewert’s article, which is reprinted in this issue, is practically the only defense of the Mennonite rejection of military service written in Germany in the last third of the 19th century. He argues for the primacy of a living faith based on the word of God and committed to Jesus as Lord. This faith should be made visible by its rejection of both concern for material possessions and striving to earn the respect of the world. It should not confuse the needs of the state or the nation with the pattern of life in the Kingdom of God. Ewert argued that the Mennonite concern for keeping the government happy so that Mennonites would be tolerated in the end crippled their faith. The key failing was the Mennonite decision to stop reaching out in mission to their neighbors out of fear that baptizing outsiders who would then also reject military service would draw the government’s wrath on the whole community. Yet with no outsiders ever joining the church, physical birth into a Mennonite family became the hallmark of the church, not spiritual rebirth as children of God. A church that puts its light under a bushel so it can stay safe will take on an earthly spirit, not a heavenly one. Thus, he was appalled that Jakob Mannhardt could argue that Mennonites killing and dying for the German Empire was the equivalent of Jesus dying on the cross. For Ewert this was mixing up the earthly and heavenly realms. Jesus came to save the French and the Germans, not to inspire Germans to kill the French.

By the time his article was printed, he was in North America as the only Prussian delegate to join those from Russia who were looking for new settlement areas. Ewert visited Manitoba, the Dakotas, Nebraska, Iowa, Kansas, and Texas as well as Mennonites living in Illinois, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. He did not spend much time in Manitoba and was unimpressed with the loose attitudes toward alcohol he found there. He set his heart on Marion County already during this first visit. He arrived there in 1874 with the main wave of migration from Russia while most other Prussians only came in 1876 and settled east of Newton, Kan., or west of Beatrice, Neb. Only a handful migrated with him from his own quite small congregation, including the Franz Funk and Cornelius Jantz families.[8]

After arriving in Kansas and establishing the Bruderthal congregation, Ewert was active in wider Mennonite activities. He chaired the Kansas Conference of Mennonites for seven years. He encouraged mission work and especially education. His son Heinrich was a teacher at the Halstead (Kan.) Seminary from its inception in 1883 until he was called to start the Mennonite Collegiate Institute in Gretna, Manitoba, in 1891. Wilhelm was a key supporter of the Halstead school and its successor, Bethel College, although he died in June 1887, just as Bethel was getting organized.[9]

Wilhelm’s wife Anna Jantz died a few months before him. Both were buried in the Bruderthal cemetery. Their graves were moved to the Haven of Rest cemetery east of Hillsboro when the Brudertal church and cemetery was flooded by the Marion County reservoir project in the 1960s.

The Ewert monument today in Marion County, Kan.

NOTES

[1] Cornelius Krahn, “Ewert, Wilhelm (1829-1887).” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online, https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Ewert,_Wilhelm_(1829-1887)&oldid=118163. Wilhelm Ewert’s papers are available at https://mla.bethelks.edu/archives/ms_6/

[2] Details of this process are available in Mark Jantzen, Mennonite German Soldiers: Nation, Religion, and Family in the Prussian East, 1772-1880 (Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, 2010), 191-228.

[3] http://etnomuzeum.pl/parki-etnograficzne/olederski-park-etnograficzny/

[4] The Bürgerschule was roughly the equivalent of junior high today, and oriented to skilled trades and business pursuits. Nonetheless Ewert received more schooling than was typical in the day, a sign of interest in education in the family and some wealth.

[5] David Goerz, “Nachruf,” Christlicher Bundesbote, 15.7.1885, 4; Wilhelm Ewert, “Die Mennoniten-Gemeinden in Polen”, Mennonitische Blätter XI, no. 6 (Juli 1864), 46-48, XI, no. 7 (Juli 1864), 53-54; Family history notebook, Mennonite Library and Archives, https://mla.bethelks.edu/archives/ms_6/045%20Family%20history%20notebook/pages/25.php, Wilhelm Ewert Grandma Online number 47130; Mildred Hansen, “Stories about Auguste Ewert Rempel,” 2.

[6] “Translated from number 1 churchbook of the Bruderthal Congregation, at Bruderthal, Marion County, Kansas,” typescript, Mennonite Library and Archives, Bethel College, North Newton, Kan., 2-3; Jantzen, Mennonite German Soldiers, 200-212, 222-23. Penner’s second known writing on the issue of nonresistance, recently discovered and identified here for the first time, was a March 24, 1873, letter written to the Mennonitische Friedensbote in Pennsylvania, which briefly recounted the ordeal of Johann Dyck, 17, no. 10 (May 15, 1873), 76, reprinted in the south German Gemeindeblatt der Mennoniten 4, no. 7 (July 1873), 55. On Penner’s brief clash in 1872 with Jakob Mannhardt in the pages of the Mennonitische Blätter, see John D. Thiesen, “First Duty of the Citizen: Mennonite Identity and Military Exemption in Prussia, 1848-1877,” Mennonite Quarterly Review, 72, no. 2 (April 1998), 177-80.

[7] Jantzen, Mennonite German Soldiers, 200-04, 221-27.

[8] Leonhard Sudermann, Eine Deputationsreise von Rußland nach Amerika (Elkhart, Ind.: Mennonitische Verlagshandlung), iii-iv, 10-11, 15-16, 22, 27, 67, 77, 95; Hans Werner, “‘Something…we had not seen nor heard of’: The 1873 Mennonite Delegation to Find Land in ‘America,’” Perservings 34 (2014), 11-20.

[9] Goerz, “Nachruf.”