New Heaven, New Earth: The Christian Socialist Vision of J.G. Ewert

In 1910, H.P Krehbiel, the editor of the German-language Mennonite publication Der Herold published in Newton, Kan., expressed growing alarm about another German-language Mennonite newspaper editor 25 miles to the northeast. Chief among Krehbiel’s concerns was this editor’s defense of socialist leaders, including Eugene Debs, who had made critical comments about religion. In one column Krehbiel writes, “Whoever defends (anti-Christian socialism and communism) has us as his opponent.” [1] Claiming that Krehbiel selectively translated and misrepresented Debs’ statements, the unnamed target of Krehbiel’s attack hit back in a column the following week in his own publication: “Whoever defends anti-Christian Republicanism and capitalism, has us as his opponent!” [2]

The rogue newspaper editor whom Krehbiel confronted was Jacob Gerhard Ewert, at the time the editor of Vorwärts, published in Hillsboro, Kan. Heated exchanges between Krehbiel and Ewert underscore several important characteristics of J.G. Ewert. First, Ewert was a debater at heart. As a college student, Ewert participated frequently in oratory and debating activities. He believed in the power of language to persuade, and he sought opportunities to engage in an exchange of ideas in order to get closer to the truth. Second, he was fearless, never afraid to speak his truth to power regardless of the consequences. Throughout his life he stood up to politicians, the wealthy, church leaders, and even the United States government during wartime with an undaunted courage. And finally, as is the subject of this article, he was committed to a Christian socialist vision – a fact that is unfortunately obscured by many who prefer to avoid this controversial worldview and focus instead on Ewert’s other convictions and many accomplishments. It was this Weltanschauung, however, that provided the framework for much of Ewert’s work during his remarkable and peculiar life.

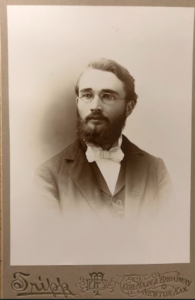

J.G. Ewert as a Bethel College student, ca. 1895-96

Born in the village of Tschonstokow in modern-day Poland in 1874, Ewert immigrated with his family in 1882 to the United States and settled in Hillsboro. [3] After a period as a stellar student in Marion County schools and a short tenure as a public school teacher, Ewert enrolled in the fall of 1895 at the recently founded Bethel College to focus on his two favorite disciplines: theology and philology.

His studies, however, were cut short due to an undiagnosed illness that left him almost totally immobilized. At the age of 25, he became completely bedridden, assuming a position that would be his lot for the next 23 years of his life. Cared for by his mother, Sara Jantz Ewert, and brother, David, he spent most of his time on his left side with only the use of his right arm from the elbow down. He describes his condition as if his entire skeleton was simply one bone. His jaw was also immoveable, but he had an eighth-of-an-inch gap between the upper and lower teeth so he could eat (but not chew). His health vacillated over the years with times of intense pain followed by periods of relief. Arthritis eventually crept into his right hand, affecting his ability to compose text himself.

The mysterious illness and failed treatments left Ewert physically, emotionally, and spiritually devastated. But after a period of despondency, he decided to get to work. From his bed he read extensively, became an expert on current events, and developed proficiency in multiple languages. His strange physical condition and his frequent public correspondence helped him achieve celebrity status in Marion County and beyond during the first decade of the 20th century. A Marion Review piece from 1908 opens with the question “Who is J.G. Evert of Hillsboro?” In addition to listing a series of Ewert’s activities and accomplishments, the writer calls Ewert “one of the most convincing writers in the state of Kansas, and so far no one has even attempted to disprove anything he has written.” [4] A writer for the Marion Headlight asks, “Are you completely absorbed with material things, or have you lost heart and hope? If so, dear reader, you need to go and learn something of life’s larger significance at the bedside of Jacob G. Ewert.” [5] Apparently many people heeded this advice; by 1910, a reported 6,000 visitors had signed a book at Ewert’s bedside. [6]

Ewert quickly turned his knowledge into activism. Despite, or perhaps because of, his physical limitations, Ewert became an outspoken critic of those who preyed on the vulnerable and a champion for various social causes. The main mouthpiece for his platform was the Hillsboro Journal, a seemingly unassuming weekly newspaper mainly serving Marion County and Mennonite communities throughout the country. Ewert was a frequent contributor and eventually took over the editorship of the paper in 1909, almost immediately changing its name to Vorwärts and adopting the motto “The Golden Rule Overcomes the Power of Gold”–both moves being not-so-subtle nods to his socialist convictions.

In a column titled “Religion and Politics,” which ran several months before Ewert became editor, he argues that while religion and politics need to remain somewhat separate, there must also be a connection between the two. Religion cannot simply be concerned with spiritual issues and ignore “earthly relationships” and “bread-and-butter issues.” A religion that fails to address temporal issues is not really a religion. He writes, “The Christian has a vibrant interest that we have a nation in which justice and peace reside.” He then identifies the biggest threats to this type of society and to the practice of authentic Christianity: capitalism, militarism, and alcoholism. [7]

Ewert does not state here or elsewhere which of these three threats he considered most destructive. He wrote numerous tracts about the dangers of alcohol, including Die Bibel und Enthaltsamkeit (The Bible and Temperance), which was published in 1901 – a revised and expanded edition appearing in 1903. He also served as the corresponding secretary of the International Temperance Bureau. His writing about temperance appears to have been quite popular, with one newspaper article claiming that he shipped 10,000 copies of one pamphlet to Illinois. [8]

Additionally, he was clearly concerned about militarism. A committed pacifist, Ewert made frequent remarks in Vorwärts promoting pacifism and expressing concern over everything from wasting money on military spending to calling army drills “war games.” The start of the First World War brought out Ewert’s activism on this particular issue even more as he defended Mennonite opposition to buying war bonds and counseled conscientious objectors. He also was a staunch advocate for the Mennonite peace position as he criticized publications like the Kansas City Star for misrepresenting the COs being held at detention camps and the military prison at Ft. Leavenworth. [9]

This activism leads James Juhnke in his insightful book A People of Two Kingdoms to conclude that Ewert prioritized pacifism over socialism. [10] I suggest, however, that Ewert saw the underlying capitalistic system as the main culprit. As a committed socialist, he undoubtedly believed that changes to the base were necessary to bring about changes to the superstructure. It is capitalism that produces despair among the people, which drives them to drink, and it is the greed of the armament industry in the relentless pursuit of profit that drives nations to war.

Ewert’s support of socialism and critique of capitalism can be found throughout Hillsboro Journal/Vorwärts. Often these comments appear in passing observations, such as this critique of the industrialist Andrew Carnegie: “The millionaire Carnegie is making a big name for himself through the libraries which he is donating and then makes his factory workers work twelve hours a day. Where should they then get the time to make use of the libraries?” [11] At other times, he provides multi-paragraph discussions of the news of the day to illustrate the destructive power of capitalism and the need for a change in economic systems.

His socialist convictions are most fully articulated, however, in his ambitious work Christentum und Sozialismus (Christianity and Socialism). [12] The first edition of this text was serialized in Vorwärts during 1909 and appeared in pamphlet form that same year. Ewert prefaces the expanded second edition, published in 1914, with his poem “Wer muss die Lasten tragen?” (“Who Must Bear the Burdens?”):

The tax burden to bear belongs to the rich parasites.

They extract only profit from nation and kingdom:

They deliver armor plates, the cannons.

Like the greedy grunter they fatten themselves

On tariffs, increasing the price of bread and clothing.

The poor alone pay the tariffs.

The rich rake in the profits.

Are you patriots? O disgrace and shame!

What an ugly spectacle you offer the land,

Living from the work of others like parasites,

Brashly burdening the people with millions.

And you bristle to carry the smallest burden.

Mammon’s servants are you, I must say!*

The aggressive and emphatic tone of the poem foreshadows Ewert’s boldness throughout the text. Ewert is bold; this is not some milquetoast criticism of capitalism and a timid statement of support for socialism. Ewert sees the current economic system as extremely harmful; he uses the biblical term mammon–a pejorative and contemptuous term for material wealth–connecting it to greed and gluttony. He repeatedly criticizes those who have given themselves over to wealth and become “Mammons Diener” (“servants of mammon”).

Capitalism tarnishes everything it touches, according to Ewert. The result is all-consuming greed for those who have money and oppression and hardship for those who don’t. The detrimental effects are felt most acutely by the most vulnerable in society:

The hardship bears down especially hard on poor women and children. Women must almost work themselves to death for a few cents a day for the honor of carving out a miserable existence. . . . Instead of going to school, children must go in droves to factory slavery, where these days more children will be sacrificed to mammon than were sacrificed to Moloch in ancient times. [13]

Ewert takes on the work of an apologist in this pamphlet, defending socialism from the inaccurate charges leveled against the movement. Ewert admits that he himself had various initial negative ideas about socialism but only because he had internalized critiques from its opponents. “All reform movements have in their beginnings a multitude of preconceived notions, misunderstandings and deliberately disseminated false representations to overcome,” Ewert writes in the opening sentence. [14] In actuality, as Ewert explains, socialism is more in line with Christian thought than the capitalist system.

To begin, he defends socialism from a variety of charges:

1) Aren’t socialist revolutions violent?

2) Aren’t socialists opposed to marriage and family?

3) Aren’t socialists antagonistic to the church?

To these and other questions, the answer is an emphatic “no.” Ewert blames this misunderstanding, in part, on the press that has been in league with capitalist powers. Socialism is not a movement to be feared. In fact, Ewert suggests, it is already functioning in American life through institutions like the U.S. Postal Service and the highway system.

He then puts forth a biblical argument for socialism. He turns the familiar argument about socialism fostering laziness on itself by quoting 2 Thessalonians 3:10b: “If any one will not work, let him not eat.” For Ewert, it is capitalism, not socialism, that fosters laziness with rich capitalists simply living off interest and dividends and the hard work of others. He quotes passages from the Old Testament, such as Isaiah 5:8a (“Woe to those who join house to house, / who add field to field, / until there is no more room”), which highlights his concern about land and wealth concentrated in the hands of the few. “The Bible says that every worker is worth his wages” (1 Timothy 5:18b), Ewert writes. “Is it not implied that he should retain the full value of what he has produced with the work of his hands?” [15] In practice, capitalism robs all legitimate workers, from the Western farmer to the Eastern factory worker.

It should be noted that Ewert is writing for a broad Christian audience. In fact, he never uses the word “Mennonite” in his text. Nevertheless, he employs a Mennonite theological approach by foregrounding the life and teachings of Jesus, especially the Sermon on the Mount. He argues that the words and actions of Jesus are clearly rooted in a socialist ethic through his actions like cleansing the temple and statements such as “You cannot serve God and mammon” (Matthew 6:24b) and “Do not lay up for yourselves treasures on earth” (Matthew 6:19a). The early church also provides evidence of the connection between Christianity and socialism. Ewert points specifically to Acts 4:32-34: “Now the company of those who believed were of one heart and soul, and no one said that any of the things which he possessed was his own, but they had everything in common. . . There was not a needy person among them . . .”

That the church has departed from these teachings and embraced capitalism should give Christians pause. Ewert asserts that Christians must humble themselves as they realize “that it was mostly unchurched socialists who first put their fingers on the sore point with the accusation that we are not living in our economic and social affairs according to Christ’s principle: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself’ (Galatians 5:14b).” [16] The church must also recognize that the rejection of Christianity from some socialists is partly the fault of the church, which has aligned itself too closely to the machinery of capitalism. Ewert argues for a third way, for a middle ground between earth and heaven:

As the Church erred in one direction by not satisfying the reasonable demands of a working class in dependency through the increase of machinery, so the socialists erred in the other extreme by believing they could shut themselves off from the demands of the spiritual side of human nature. This error on both sides has become a disastrous stumbling block, which has not only alienated many progressive-minded workers from the church but has also robbed the social movement of an element of potency, which otherwise would have helped it prevail. [17]

Despite the gulf between the two sides, Ewert believes that more Christians in various countries are realizing the interconnectedness of socialism and Christianity. “The spirit of God hovers again over the waters,” Ewert writes, “and revitalizes the moving forces with new energy. Light breaks through the darkness and mutual understanding is being initiated between the elements that were previously in conflict.” [18] The times are changing, and Ewert looks at the growth of the socialist movement in America based on poll numbers with hope. He sees the outbreak of World War I as a wake-up call for people to turn toward a different economic system. He concludes: “Whoever is in favor of the people soon getting to the place of turning their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks and learning more peace as the Bible says, he can do nothing better at the polls than to cast his vote for socialism.” [19]

Ewert’s utopian dream did not come to be, and 110 years later Ewert’s optimism can certainly seem naïve. While he remained committed to socialism, the war and its aftermath consumed much of Ewert’s time during the remaining nine years of his life and diverted his attention away from his direct advocacy for socialist reform. America’s entry into the war resulted in persecution for American Mennonites, and the Russian Revolution brought about disaster for Mennonites in Ukraine. Ewert came to the aid of both groups through his knowledge of world events, his extensive network of contacts, and his tireless efforts.

Nevertheless, his Christian socialist vision continued to inform his advocacy. While many of his contemporaries did not in the end embrace his socialist perspective, Ewert certainly challenged them to look beyond personal piety and, as Christians, to concern themselves with the temporal. One of Ewert’s favorite Bible verses appeared as part of the masthead of Vorwärts for many years. It is 2 Peter 3:13b: “[W]e wait for new heavens and a new earth in which righteousness dwells.” There is some irony, however, with the verb in this sentence as it relates to Ewert’s life. He was certainly not content with just sitting back and waiting. Physically incapacitated, he demanded action from himself and expected others to help bring this new, more just and righteous earth into existence.

*Original German, translated by the author

Seid Patrioten ihr? O Schmach und Schande!

Welch hässlich Schauspiel bietet ihr dem Lande!

Lebt von der Arbeit andrer wie die Drohnen,

Belastet keck das Wolf mit Millionen

Und sträubt euch, selbst die kleinste Last zu tragen:

Des Mammons Diener seid ihr, muss ich sagen!

Die Steuerlast zu tragen, gehört den reichen Drohnen:

Nur Vorteil ziehen Sie aus Staat und Reich:

Der liefert Panzerplatten, der Kanonen,

Der mästet sich, dem gier’gen Grunzer gleich,

Um Zolltarif, mit dem man Brot und Kleid verteuert.

Die Armen zahlen da den Zoll allein;

Die Reichen streichen die Gewinnste ein!

Notes

[1] Der Herold, May 26, 1910. All translations are from the author of this article.

[2] Vorwärts, June 3, 1910.

[3] Tschonstokow (Czosnów) is located in a region that changed hands multiple times before the modern state of Poland was established. At the time of Ewert’s birth, it was under Russian control. This village was part of the Deutsch-Kasun Mennonite area northwest of Warsaw (up the Vistula River from that city). This Mennonite settlement had been established in 1776 by people with surnames like BarteI, Schroeder, Guhr, Jantz, Plennert, and Ewert.

[4] The Marion Review, Aug. 27, 1908. It should be noted that, as a linguist, Ewert was very concerned about pronunciation in general, and specifically the pronunciation of his name. He was a proponent of changing the spelling of German names to replicate, as closely as possible, the correct pronunciation. As a result, he sometimes used a “v” in place of the “w” for the benefit of non-German speakers.

[5] Marion Headlight, June 27, 1907.

[6] “Fighting a Good Fight,” Vorwärts, July 8, 1910.

[7] Hillsboro Journal, Dec. 4, 1908.

[8] Marion Headlight, Aug. 6, 1908.

[9] Topeka Daily Capital, June 3, 1918.

[10] James C. Juhnke, A People of Two Kingdoms: The Political Acculturation of the Kansas Mennonites (Newton, Kan.: Faith & Life Press, 1975), 70.

[11] Hillsboro Journal, May 21,1909.

[12] J.G. Ewert, Christentum und Sozialismus, 2nd ed. (Hillsboro, Kan.: Hillsboro Job Office, 1914).

[13] Ibid, 2-3.

[14] Ibid, 1.

[15] Ibid, 3.

[16] Ibid, 8.

[17] Ibid, 8.

[18] Ibid, 9.

[19] Ibid, 17.