The History and Legacy of the Old Flemish Mennonite Congregation of Przechówko

More than 4,000 Mennonite immigrants arrived in the central United States between late 1873 and January 1875. A large proportion of those immigrants had ancestors originating from the Przechówko Mennonite congregation in Poland. Already with the very earliest ships arriving in summer 1873, there were Przechówko-descended people, but the largest batches came in the summer of 1874 aboard the S.S. Cimbria, the S.S. Teutonia, and the S.S. Vaderland, which in a very basic sense established the communities of Alexanderwohl, Hoffnungsau, and Lone Tree, respectively, in central Kansas. Since Przechówko descendants made up an estimated ~60% of the 1873-75 immigrants (1), it’s crucial to know more about this formative community, village, and congregation, during this 150th-anniversary year.

History of Przechówko

Beginning before the mid-point of the 16th century, Low German Mennonites began coming into the Vistula River delta area, specifically to the northern cities of Danzig (Gdańsk) and Elbing (Elbląg). They migrated into Polish Prussia from the Dutch Lowlands. These Mennonites sought economic opportunities as well as religious liberty. Royal Prussia at this time was a semi-autonomous province controlled by the Polish Crown. The Mennonites generally came to live in the area under charters authorized by Polish kings, which allowed them a level of religious tolerance and economic freedom.

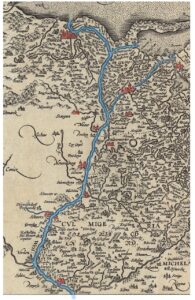

The Lower Vistula River Valley; Prussiae Vera Descriptio, Jan Baptista Vrients. Antwerp, 1608. Cropped.

Cities along the Vistula, such as Danzig, Elbing, and Thorn (Toruń), were close trading partners with the Dutch, so there were already ties between this area and the lowlands. The lower Vistula floodplains were susceptible to annual flooding – local landowners were keen to import Dutch farmers who knew how to tame floodwaters. The Low German Mennonites were masters of building dams, dikes, pumps, and canals, so they were welcomed all along the lower Vistula and soon came to control a large proportion of the land in the lower 90 miles of the river.

Initially, there were 14 Mennonite congregations in the area. These 14 were the homes of the ancestors of almost all Low German Mennonites. There was a dense concentration of nine congregations in the delta, while the other five were spread out along the valley. These Mennonite congregations along the Vistula were divided basically into two sects. The delta was dominated by the Flemish sect, and the valley by the Frisian sect. The only Flemish congregation in the valley – an Old Flemish congregation – was located at Przechówko. Congregants at the Przechówko church included Low Germans originating from the Dutch Lowlands, Germans originating from various areas of Germany, and a certain number of native Kashubian or Pomeranian people originating in lands adjacent to and slightly west of the northern Vistula River.

Przechówko was located on the left bank of the river about 60 miles south from the Baltic Sea coast and was likely established right about the year 1600. (For context, Shakespeare’s tenth play, Romeo and Juliet, was first published in 1601, while the Colony of Virginia was established in North America as the first permanent English colony in the New World in 1607.) (2)

The Schwetz Lowlands, 1893; 1893 Schwetz Niederung Composite Map (KDR 100_194 Crone a.d. Brahe; KDR 100_195 Graudenz). Edited by Rodney Ratzlaff.

Since the village of Przechówko was established late in the 17th century, it never did have a German name like many other villages where Mennonites lived; the Mennonites always would have called it “Przechówko.” This name is actually a diminutive derived from the larger adjacent village of Przechowo. After the establishment of the German Empire in 1871, the village was renamed Wintersdorf, but since they had left the area by that time, the Mennonites would have never used this name. The early Low German Mennonites settled in villages such as Przechówko that were located in the river lowlands. Przechówko itself was located within the Schwetz-Culm (Świecie-Chełmno) lowlands, about 1½ miles north of the Vistula River channel. The village, along with neighboring Deutsch Konopat, Dworsyzko, Głogówko, and others, was situated on a large sandbar terrace on the river’s left bank. Głogówko sat right down on the floor of the floodplain while the others were only a maximum of 12 feet elevated above the floodplain floor.

These lowlands were highly vulnerable to flooding, so the people had to be adept at building dikes, pumps, and canals, and vigilant in maintaining the systems they put into place. The management of the river floods affected almost every part of their lives. The area was crisscrossed by a network of dikes and canals, the maintenance of which was top priority for every villager. Careful systems were put into place to monitor the integrity of the dikes and other flood mitigation systems.

The Przechówko church was located within the tiny village of Przechówko. Usually, Przechówko comprised only 12 farms, so congregants lived in many surrounding villages as well. These villages were laid out differently than Mennonites may be accustomed to seeing in the Molotschna Colony, for instance. In these Polish villages, houses were irregularly spaced one from the next and were not situated in nice, straight lines. Houses might have been separated by 50 yards or more. Villages were essentially nothing more than a collection of houses with a borderline drawn around them. Typically, waterways such as canals, ditches, or streams made up borders between villages. Przechówko congregants lived in many adjacent villages. On the left bank they were found in Deutsch Konopat, Głogówko, Beckersitz, Niedwitz, Dworzysko, and others, while on the right bank they were found in Dorposch, Ostrower Kaempe, Neusass, Ober and Nieder Ausmass, Jamerau, Schönsee, and others. Most of the villages were inhabited by Mennonites as well as native Polish Catholics or German Lutherans; Przechówko was the only village inhabited exclusively by Mennonites. (3)

In Schönsee there was an Old Flemish congregation that became associated with the Przechówko church by the 18th century. In the same village there was also a Frisian Mennonite congregation, so in some of the right bank villages there were Frisians and Old Flemish living side by side. There is evidence of these mingling to a degree. Some Frisian families, such as certain Schroeder and Nickel families, even joined the larger Przechówko daughter movements in Volhynia and Molotschna in the Russian Empire.

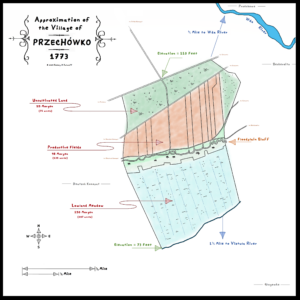

Approximation of the Village of Przechówko, 1773, Rodney D. Ratzlaff, 2023.

Przechówko in the late 18th century was an irregularly shaped village that included fields, yards, and lowland meadow. To the west, it was bordered by the village of Deutsch Konopat; to the north by a small forest; to the northeast by the Wda River and by the larger village of Przechowo; to the east by additional lands owned by Przechowo as well as other lands belonging to the settlement of Beckersitz. The total area of the village land was equivalent to ~418 acres. The whole area gently sloped downwards north to south; the elevation at the north was ~110 feet above sea level and the elevation at the canal in the south was ~73 feet above sea level. The land in the far north was uncultivated and was highly vulnerable to flooding from the Wda River. This distance between the northern boundary and the Wda was only ~1/3rd mile and there was no dike there.

The central ~135 acres was the cultivated land for growing crops. Here they grew almost exclusively rye. In some neighboring areas, wheat, barley, oats, and peas were also grown. The soil in Przechówko was not the rich silt found in some other areas along the river. Przechówko soil had a very high sand content, so it was not ideal for growing crops.

The houses stood along the central road. The width of the village along the road was ~2/3rds of a mile. The road was a couple slight S-curves and dipped gently up and down. The houses stood right on the edge of a natural terrace. South of the houses, the downhill slope became sharper into the lowland meadow. This meadow was extremely wet and likely good for only one crop of hay each year. There were numerous ditches cut into it, which helped to drain water. In the meadowland, the Mennonites would graze cattle and horses, and harvest flax and hay. They had a fair number of dairy cows – dairy products were their primary source of income. The flax they harvested would be spun and woven into linen.

The whole area was divided into plots. Each farmer had his own plot, which varied in size from one farm to the next. There were ~418 acres total, and in 1773 each farmer had an average of ~34.8 acres of total land: ~11.25 acres of cultivated land and ~23.6 acres of uncultivated and meadowland. (4)

The central village road in Przechówko ran roughly east to west and another road stretched out north from the center. The cemetery was located on top of one bluff – on the top of the natural terrace – and on top of the next bluff to the east was the church building. To the north of the road was the cultivated land and beyond that, the uncultivated land. (5)

Przechówko Village sketch, Rodney D. Ratzlaff, 2023.

The terrace – or row of bluffs at the center of the village – was about 15-20 feet high. Immediately south of this terrace were the village houses. The houses stood on areas of land that had been leveled. Immediately south, the ground dropped away again. Each house likely had a large garden, which included fruit trees and various kinds of vegetables. To the south of the gardens, the land sloped downward into the lowland, which was the marshy meadow area. Today, all this area is covered with trees, as well as by the Mondi cardboard factory. When the Mennonites lived in the village, there would have been very few trees, but today the area is so thick that one has a very difficult time gaining a proper perspective of the topography.

The Mennonites would have lived in housebarns in Przechówko, although no structures still stand there now. We know roughly where the church stood but we don’t know exactly what it would have looked like. We do have photos of Hollander housebarns in Przechówko, Wielki (Deutsch) Konopat, and Jeziorki, from the mid-1960s. The best example from Przechówko, interestingly, is strikingly similar to the Niedwitz (Niedźwiedź) house that has been restored and is today found at the Hollander Museum (Olenderski Park Etnograficzny) at Wielka Nieszawka near Toruń. This particular Przechówko structure was quite large, while those in Konopat and Jeziorki were smaller. (6)

Przechówko housebarn; Przechowko dom (chałupa) nr 141 (16); https://zabytek.pl/pl/obiekty/dom-(chalupa)-nr-141-(16-875964, 3 July 2024.

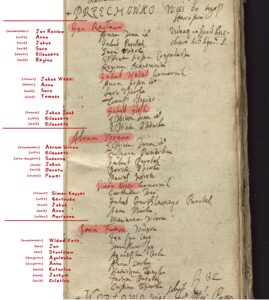

A tax list from 1662 gives us an idea of the village in the very early years. (7) The master of the first house is Jan Raclaw. This would be the son of the Ratzlaff soldier we read about in the Przechówko church records; the man who deserted the Swedish military and thrust his sword into the hedgepost. Jan Raclaw has a wife named Anna, a hired hand named Jakob and a maid named Sara. His sister Elisabeth lives with the family, and she has a maid named Regina (these hands and maids are likely local Polish youths). In the same house, we have Jacob Wedel with his sister Anna and their maid and hand, Sara and Tomasz. Still in the same house, we have Jacob Isaac with his wife Elisabeth and their maid Elisabeth.

1662 Przechówko Census; Regestrum subsidii g[ener]alis palatinatus Pomeranie cum sius dismetibus, 1662. Sygnatura 1/7/0/3/147. Archiwum Główne Akt Dawnych w Warszawie, Archiwum Skarbu Koronnego.

The third house is home to the Widow Voth with her sons Jan and Stanislaw (this name doesn’t make sense because this is a Polish Catholic name) and daughters Anetta and Anna, with hands and maids named Katarina, Jachym, and Cristina. Children are not listed on this record since this is a tax list showing only people who would have been liable for taxes.

Notably, there are only three houses occupied in the village at this time. This very much reflects the conditions in the early 1660s. The area had only very recently emerged from wars with the Swedes, which had destroyed cropland, killed livestock, and generally de-populated the countryside. The likelihood is that after a few years some of the population would have returned and there would have been more houses occupied in the village. In fact, we do have a couple of lists from the first decades of the 18th century indicating residents living on all 12 farms. (8)

1773 Przechówko Cadastre; Przechowka Village, 4 March 1773. Extracted by Glenn H. Penner, Translated by Sabine Akabayov. https://www.mennonitegenealogy.com/prussia/1772/Przechowka.pdf. 30 December 2022. https://www.mennonitegenealogy.com/prussia/1772/West_Prussia_Census_1772.pdf. 18 April 2023. See also Baue und Reparaturen an den Kirchen-, Pfarr- und Schulgebäuden zu Przechowko, 1854-1857. I. HA Rep. 76, IX Sekt. 5 Lit. P Nr. 41. Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz.

Another fascinating record for the village – a cadastre – was completed in March of 1773. This cadastre shows the emphyteutic leaseholders living in the village (12 families) as well as the einwohner or einlieger (4 families). The cadastre also lists statistics for the settlement of adjacent Beckersitz, which was actually located on land owned by Przechówko. The farmers were Hans Funk; Peter Unrau’s widow; Hans Unrau; Tobias Ratzlaff; Andreas Pankratz; Heinrich Unrau; Benjamin Wedel; Peter Becker; Abraham Richert; Jacob Cornels; Hans Ratzlaff; and Jacob Pankratz. The einlieger families were Peter Ratzlaff; Hans Schmidt; a second Peter Ratzlaff; and finally the widow of yet another Peter Ratzlaff. The cadastre is particularly interesting because it lists how much land each farmer held, how much grain he planted, what the condition of the land was, how much hay was gathered in the meadow, if there were lakes and whether the villagers may fish, and so on. (9)

For genealogical purposes, this cadastre is very valuable – we can easily determine who each farmer was and find him in the GRanDMA database as well as in the Przechówko church records. The families were heavily interrelated. Extended family to many can also be found in similar cadastres for the nearby villages of Deutsch Konopat, Głogówko, or Jeziorki. It’s also notable how many of the surnames listed are still common in descendant communities today.

Legacy of Przechówko

Since so many of the 1874 immigrants to the United States descended from this village and congregation, it’s key for Low German Mennonites in the midwestern USA to understand the importance of their Przechówko origins. The congregation holds a unique place in Low German Mennonite history and in places like central Kansas its legacy can still be felt today. Przechówko’s unique legacy can be defined by four characteristics:

1) the proclivity of this congregation to spawn daughter congregations;

2) the remarkable consanguinity of the members of the daughter congregations;

3) the extensive church records of the original congregation and the continuation of those records right into the present day;

4) the Przechówko village cemetery.

Due to various reasons – lack of land, lack of economic opportunities, oppression from landowners or local officials, turmoil after wars, religious oppression, and others – Przechówko congregants began to expand into daughter congregations very early on. Notably, the Przechówko congregation was the only Low German Mennonite congregation to repeatedly spawn daughter congregations made up almost exclusively of people with ancestry from the mother congregation. This is a trait of the Przechówko community that has been unique. (10)

Przechówko was established right about the year 1600. Very early on, it became associated with the Old Flemish congregation located in Schönsee, although this probably was not a true daughter or expansion congregation. The first true daughter congregation to Przechówko was Jeziorki, established about 15 miles to the northwest in 1727. The next expansion was in the Neumark – Brenkenhofswalde and Franzthal – established in 1765. Under the Polish Kingdom, two more daughter congregations were established: in Masovia at Sady, and in Podolia at Deutsch Michalin. Both of these were established very late in the 18th century and Deutsch Michalin likely was an outgrowth from the Masovian communities. All these congregations were established by Przechówko congregants, and all these congregations continued to commune with the mother church. (11)

Beginning in 1801, the first Przechówko daughter congregation established within the borders of the Russian Empire was formed at Karolswalde in Volhynia. A second Volhynian colony was established at Antonowka in 1804. In the same year, the Molotschna Colony was established in New Russia and, beginning in 1820, the larger group at Przechówko began moving into the Molotschna Colony. These folks established the villages of Franzthal and Alexanderwohl in 1820 and 1821 respectively. The Neumark villagers established the village of Gnadenfeld (Molotschna) in 1835. Some of these Neumark-Volhynians moved to the Molotschna Colony in 1836 to form the village of Waldheim (Molotschna). All these villages in Volhynia and Molotschna – that is, Antonowka and Karolswalde, and then Franzthal, Alexanderwohl, Waldheim, and Gnadenfeld – were initially made up of majority Groningen Old Flemish Mennonites and were likely all in fairly close contact with one another. Just like a family creates a family tree, the Przechówko congregation created a congregational tree. Today, congregations such as Lone Tree, Alexanderwohl, and Hoffnungau are branches of this larger tree.

Descendants of the Groningen Old Flemish of Przechówko; Rodney D. Ratzlaff, 2023.

This constant spawning of daughter congregations means that Przechówko families have a unique and special genealogy. There is likely no other large group among the Low German Mennonites that has sustained itself like the Przechówko Old Flemish have. These daughter congregations display a remarkable consanguinity. That is, a great many of the congregants can still today – more than 400 years after the birth of the congregation – trace their ancestry back to the very first congregants.

For instance, I’ve polled 150 individuals from the 1983 Alexanderwohl church book, which was about 20% of the congregation at that time. Thirty-four percent of those surveyed in 1983 still had those original Przechówko surnames; a whopping 87% had ancestors found in the village of Przechówko or at the Przechówko church; 52% had either three or four grandparents with Przechówko ancestry. (12)

We could do a very similar study with the congregants at Lone Tree Church of God in Christ Mennonite (Holdeman), with even more shocking results. From the 2020 membership list at Lone Tree, I surveyed about 55% of the total and found that 94% had Przechówko ancestry and 79% had either three or four grandparents with Przechówko ancestry. So again, in the year 2020, an estimated 94% of Lone Tree members could all trace their ancestry back more than 400 years to the same place and to the same group of people. (13)

This quality of consanguinity is likely unique among Low German Mennonites. But you’ll find it again and again, albeit to perhaps lesser degrees, at Hoffnungsau (Inman, Kan.), and Henderson, Neb., and Freeman, S.D., and Tabor Mennonite Church (near Goessel, Kan.), and at many other Holdeman congregations in addition to Lone Tree, or any other church that ultimately derives its origins from Przechówko. This is an incredible characteristic of the legacy of the Przechówko church and community.

The third point that illustrates the legacy of the Przechówko church is the presence of the extensive church record, which dates all the way back to the 17th century and in many cases can be corroborated by other documentation. Only three sets of comparable Polish Mennonite church records have come down through history to us: those from Danzig, those from Montau, and these from Przechówko. Neither the Danzig church nor the Montau church formed daughter congregations, so their records terminated when those churches came to an end.

On the other hand, the Przechówko church records were continued in the Molotschna Colony at Old Alexanderwohl. Then when that group came to USA in 1874, the record was brought to Kansas and continued. With this record, a historical document exists that spans three countries and two migrations, and covers almost 400 years of people and history. Some people in these communities can trace as many as 13 continuous generations of ancestors – or even more – through these records.

The Przechówko village cemetery is something that we’re just now coming to know. Since there are no Mennonite structures still standing in the village of Przechówko, the cemetery is the only remaining physical remnant from the 200+ years that the Mennonites lived there.

The vast majority of the Przechówko Mennonites left Prussia for the Molotschna Colony by the mid-1820s. When they left, the village became occupied by Lutheran Germans who would have lived in the Mennonite houses and buried their loved ones in the village cemetery. The last adherents to the Przechówko Mennonite church left the area entirely by the 1840s, although some Mennonite names could still be found in the immediate area right into the 1930s.

The 20th century was not kind to Przechówko; the whole area endured two World Wars and 40 years of domination by Communists. In 1964, the final village residents were evicted to make way for the Mondi cardboard factory, which today occupies the former northern half of the village. These factors greatly obscured the ability to discern what had become of Przechówko. We in America had no way of knowing what had happened – or what was happening – to the village. By the late 1980s, opportunities began to open up and travelers from the West began to go into Poland. However, the Przechówko cemetery lay apparently forgotten, hidden away in the weeds and trees south of the cardboard factory. Rumors abounded that the factory had destroyed the cemetery but seemingly no one outside the area knew for sure.

By 2019, when I first went to Poland, most American experts still weren’t entirely sure about the status of the Przechówko cemetery. But if anything was there at all, it was located off main roads, so tour groups could not easily gain access. I was fortunate enough to have a chance encounter with the Polish expert on Mennonite culture in the Vistula River valley, Dr. Michał Targowski. After Targowski took me to the cemetery, we began a robust discussion for many months regarding how to go about restoring the place. Our plans finally began to be implemented during the summer of 2023.

Przechówko Cemetery, 2024; Rodney D. Ratzlaff, 2024.

The cemetery is located centrally on land that was Przechówko village, on the south side of the road just west of where the church stood. My estimate is that it’s about 145 feet (E to W) by about 85 feet (N to S) in size. According to records, there should be well over 400 burials in the cemetery – both Mennonite and Lutheran – about half of that number being small children. (14)

Workers in the cemetery started the restoration work by clearing weeds and stray trees and undergrowth and then locating all the grave markers. When they started, it was possible to identify 73 grave markers but by September, they had discovered almost 50 additional markers.

Quickly we learned a significant characteristic about the Przechówko cemetery that makes it entirely different from other Mennonite cemeteries in Poland. For instance, Heubuden (Stogi) cemetery near Malbork may be a typical Mennonite cemetery in Poland. Mennonites at Heubuden placed in their cemetery very large gravestones, likely carved by professional masons. The inscriptions are relatively easy to read, and the vast majority of the stones are from the 19th century.

On the other hand, many Mennonite gravestones still exist in the Przechówko cemetery but they are completely different than what’s found at Heubuden. At Przechówko, the gravestones are simple field stones with crude inscriptions, probably carved by the villagers themselves. These stones represent the 18th century, in contrast to Heubuden, which reflects the 19th century.

Przechówko gravestones; Pamięć Przechówka, https://www.facebook.com/przechowkomemory, February 2024

And that’s very significant, because by today – the 21st century – it’s apparently rare in Poland to find 18th-century gravestones still in their original spots in a cemetery. Most 18th-century gravestones – or even older ones – have either been removed to museums or destroyed altogether. For instance, at the large Mennonite cemeteries at Schönsee or Obernessau, there might be only one or two 18th-century gravestones. But at Przechówko, by my count right now, there aren’t just one or two or three of these old gravestones – by my count, there are 28 gravestones that date from the 1700s, representing many lives that easily date even into the 1600s. (15) This is a totally unique characteristic of this cemetery, which really makes it quite an astonishing historical treasure.

In the summer of 2023, we were fortunate enough to have a lunch meeting with several authorities from the city of Świecie, the municipality that now owns the cemetery. Mennonite ancestors in Przechówko would have known the city by its German name – Schwetz – and it’s probably where they would have gone to market or to conduct legal business. We had a lunch in Świecie with several city authorities, including the mayor, and it was a great honor to meet these folks. The mayor pledged to keep the cemetery maintained so it will continue to be preserved. I was also able to meet with the head of the Lower Vistula River Parks Complex who offered to build a fence around the cemetery to help protect it. For these and other reasons, I’m hopeful that now we’ll be able to preserve this cemetery, which is easily the oldest Low German Mennonite cemetery in all of Poland.

It is very important, on the occasion of the 150th immigration anniversary, to understand the significance of Przechówko within the history of the Low German Mennonites. Mennonite ancestors lived in Przechówko for more than 200 years. Due to the preservation of records, the preservation of lineages, and the preservation of the cemetery, Przechówko may be the most-well preserved of all the Low German Mennonite congregations of Poland. Przechówko holds a very special and unique place within Low German Mennonite history. Mennonite communities across the central United States are very fortunate to be part of that story.

View this speech on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6g5VVv5xGmA

Notes

(1) These are my own estimates from the 38 ships carrying Mennonites to the USA between August 1873 and January 1875. GRanDMA OnLine (https://grandmaOnline.org): GMOL v7.5.12; K. L. Ratzlaff, Lawrence, Kan., 11/2000‑2/2024; Haury, David A. (compiler/editor). Index to Mennonite Immigrants on United States Passenger Lists, 1872-1904; Ship Lists, 1872-1904. North Newton, Kan., 1986; Mennonite Ship Lists 1872-1904. Compiled by J. Hubert and J. Thiesen. http:///odessa3.org/collections/ships/link/mindiv.txt, February 2024.

(2) “Visitationes Archidiaconatus Pomeraniae Hieronymo Rozrażewski Vladislaviensi et Pomeraniae : Episcopo Factae (vol. 2).” Towarzystwo Naukowe w Toruniu; Fontes 2 (Torun 1898), p. 341. There is no clear evidence of Hollander or Mennonite settlement in the Świecie, Chełmno, Grudziądz, Toruń area any early than 1565. Further, other Mennonite settlements nearby to Przechówko, such as Schönsee, traditionally dated into the mid-16 th century, also likely originated between the years 1595-1610. The Przechówko church records do not list birth dates for the very earliest Mennonite villagers. However, logical extrapolation of birthdates from their descendants indicates the earliest settlers could have been born no earlier than the first decade of the 17th century.

(3) Przechówko village, 4 March 1773. Extracted by Glenn H. Penner, Translated by Sabine Akabayov. https://www.mennonitegenealogy.com/prussia/1772/Przechowka.pdf. 30 December 2022. https://www.mennonitegenealogy.com/prussia/1772/West_Prussia_Census_1772.pdf. 18 April 2023. See also Baue und Reparaturen an den Kirchen-, Pfarr- und Schulgebäuden zu Przechówko, 1854-1857. I. HA Rep. 76, IX Sekt. 5 Lit. P Nr. 41. Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz.

(4) Przechówko village, 4 March 1773.

(5) Przechówko village 1961(ZDJ_1961_B/W_20_3483_459351); https://pzgik.geoportal.gov.pl/imap/?gpmap=gpZdjecia, 3 July 2024.

(6) Przechówko dom (chałupa) nr 141 (16); https://zabytek.pl/pl/obiekty/dom-(chalupa)-nr-141-(16-875964, 3 July 2024.

(7) Regestrum subsidii g[ener]alis palatinatus Pomeranie cum sius dismetibus, 1662. Sygnatura 1/7/0/3/147. Archiwum Główne Akt Dawnych w Warszawie, Archiwum Skarbu Koronnego.

(8) Richert, John D., “Przechowka Gemeinde Households in the Vicinity of Schwetz, 1715 and 1719.” 2018.

(9) Przechówko village, 4 March 1773.

(10) Long and numerous discussions between the author and Dr. Glenn Penner attest to this fact. Dr. Penner is the foremost genealogist among Low German Mennonites and commands a wide array of knowledge about the original congregations.

(11) For an example of the ways in which daughter churches continued to communicate with the mother congregation, see Richert, John D., “Wilhelm Lange Letters 1815-1820.” 2021.

(12) Alexanderwohl Mennonite Church pictorial yearbook, Goessel, Kan., 1983.

(13) Lone Tree Church of God in Christ Mennonite (Holdeman) church, Galva, Kan., 2020.

(14) Death records 1775-1829; Evangelische Kirche Schwetz (Krst. Schwetz). n.d. Ancestry.com. 18 April 2023. Note that there will also be some Catholic burials in the cemetery in the form of local Polish hands or maids who passed away while employed by the Mennonites.

(15) Pamięć Przechówka, https://www.facebook.com/Przechówkomemory February 2024.